"The five chief roads of Ireland, namely Slige Assail, Slige Midluachra, Slige Cualann, Slige Dala, Slige Mór. Slige Assail, in the first place, Assal son of Dór Domblas found it before the brigands of Meath when proceeding to Tara. Slige Midluachra, then, Midluachair son of Damairne son of Diubaltach son of the king of Srub Brain, found it when proceeding to the Feast of Tara. Slige Cualann, Fer Fí son of Eogabal found it before the elfmound’s armed hosts when going to Tara. Slige Dala, Setna Seccderg son of Durbaide found it before the warlocks of Ormond, when going to Tara. Or it is Dala himself that discovered it for him. Slige Mór, that is, Eiscir Riada, ’tis this that divides Ireland in two, namely from Áth Cliath Cualann (Dublin) to Áth cliath Medraige (Clarin Bridge near Galway). Nár son of Oengus of Umall found it before the champions of Irrus Damnonn, when contending for leadership, so that they might be the first to arrive at Tara. On the eve of the birth of Conn (of the Hundred Battles) these roads were found, as saith (the tale called) Airne Fingin." The Prose Tales in the Rennes Dindṡenchas translated by Whitley Stokes, UCD.ie

According to legend, there were five great roads which led to the Hill of Tara. It has always been believed that the Hill of Tara was the royal residence of the High Kings of Ireland; after all, we have inherited a vast wealth of early Medieval literature which tells us so. However, since the 1980s, a new school of thought began to emerge which interpreted these medieval tales as a reflection of the times in which they were written rather than the Iron Age which they claim to portray.

When you look at what was going on in Ireland during the Medieval period, this concept cannot be denied, but I also think these early writers were building on something which was already in existence: non-literate societies share their knowledge, learning and history through an oral tradition, and there is no reason to suppose that the people of Ireland’s pre-history were any different.

In 1992, the Discovery Research Programme found that the archaeology at Tara did not support the literature; there was no evidence of habitation, and in fact the presence of burials, combined with the density and complexity of other structures, and lack of defensive features suggested instead a ritual purpose.

It also shares similarities with other so called ‘royal sites’ at Cruachan in Connacht, Emain Macha in Ulster, and Dún Ailline in Leinster, such as the conjoined figure-of-eight mounds accompanied by the close proximity of a burial mound, both located within a wide, circular embankment and ditch.

In addition, archaeology revealed something else; that all these sites shared a mysterious decommissioning process around the year 96BC. It seems each site was buried beneath a layer of stones and boulders, the whole thing set alight, and then, when the embers had died down, the whole site was covered in earth. It was, in effect, a triple death, something which has been interpreted as a great sacrifice when applied to people, as described in literature, and as discovered during the study of various bog bodies.

Another feature shared by these ‘royal sites’, but less sensational and certainly long neglected, is their connection via a system of five great roads, which according to early Irish literature, appear to centre on the Hill of Tara.

This is what the Annals of the Four Masters has to say about them:

The night of Conn’s birth [Conn Cétchathach, meaning ‘of the Hundred battles] were discovered five principal roads leading to Teamhair [Irish for Tara] which were never observed till then. These are their names: Slighe Asail, Slighe Midhluachra, Slighe Cualann, Slighe Mor, Slighe Dala. Slighe Mor is that called Eisir Riada, i.e. the division line of Ireland into two parts, between Conn and Eoghan Mor.

(AFM M123.2).

Although travel is frequently mentioned in early Irish literature, with stopping points and places of habitation along routes being named, the roads taken are not. ‘The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel’ is an exception; it mentions ‘the four [not five] roads whereby men go to Tara’, naming two of them later in the story when Conaire breaks his kingly geisa, or taboos:

'Great fear then fell on Conaire because they had no way to wend save upon the Road of Midluachair and the Road of Cualu.'

(CELT).

Could these roads mentioned in early Medieval writings have existed in pre-historic times? For an answer, we need to turn to the archaeological evidence.

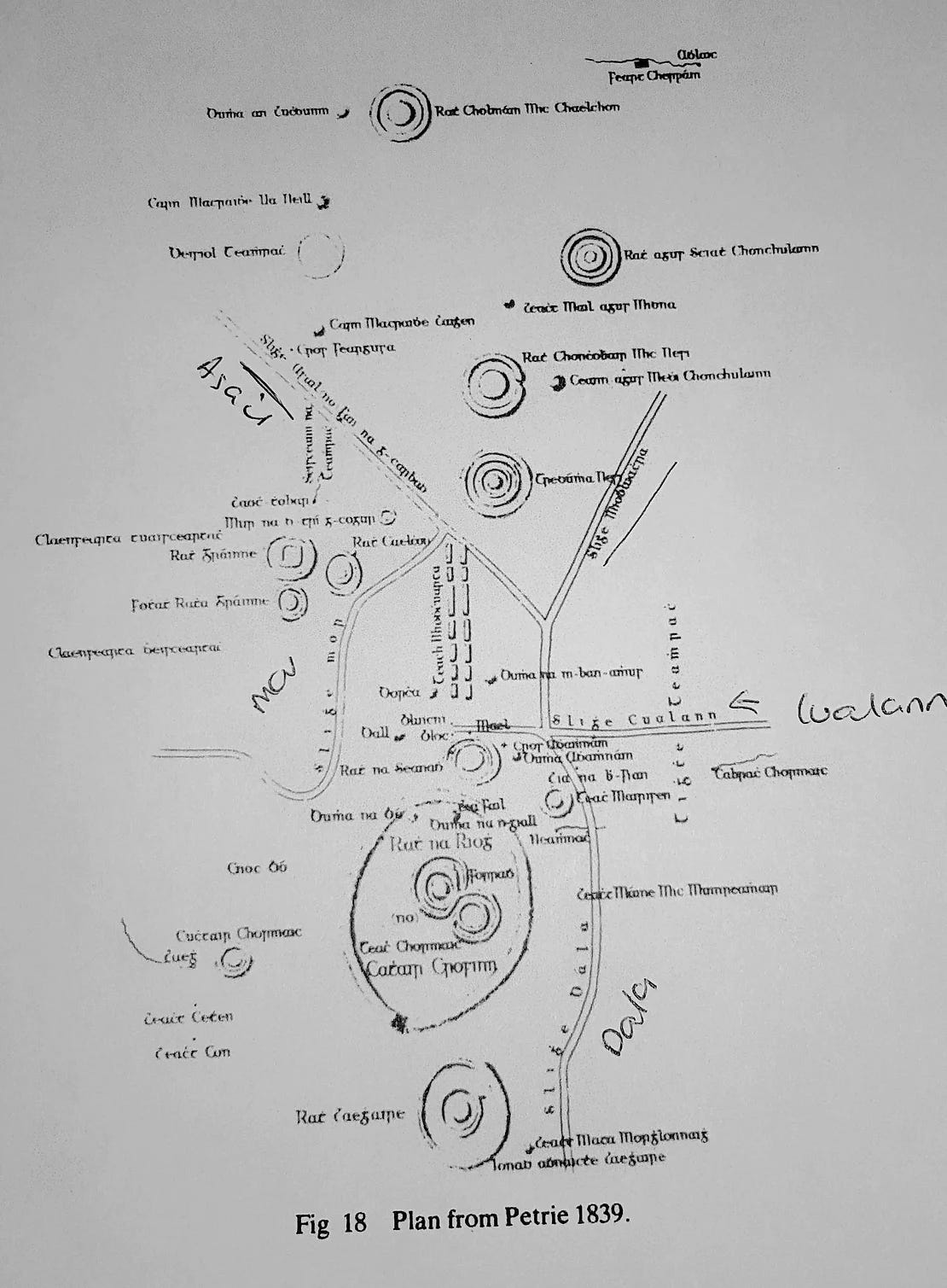

George Petrie was an Irish artist and antiquarian who travelled the length and breadth of Ireland, recording the land’s ancient monuments. In 1839, he was commissioned by the Irish Ordinance Survey to conduct a survey of the Hill of Tara, which was later published by the Royal Irish Academy. His plan clearly shows all five roads as named in the Annals.

According to scholar DL Swan, these roads ‘correspond closely to the main road system at present in use’. However, he claims the evidence upon which Petrie based his map is not clear, and that he cited none at all for his plotting of the Slighe Cualann.

By contrast, Colm O’Lochlainn‘s study, ‘Roadways in Ancient Ireland’ (1940) upon which most contemporary works are modelled, focused on journeys in early Irish literature, particularly The Tripartite Life of St. Patrick, the Tain bo Cuailnge, Mesca Ulaidh, Acaldamh na Senórach, the Book of Lismore, and others.

He marked these routes on a map upon which he had already identified place names associated with travel, such as ath– a ford; droichead – a bridge; bealach– a gap/ passage; and bóchar– a cattle track, amongst others. The results led him to identify the five great roads, but with one huge difference: they centred on Dublin not Tara, and as we all know, Dublin did not become a major centre until the Vikings in the mid ninth century.

DL Swan’s aerial photography identifies a series of linear depressions which correspond with Petrie’s plan. He also makes a very interesting observation; he claims they all align with the feature known as the Teach Miodhchuarta, or Banqueting Hall, stating that ‘regardless of which route one uses to approach the hill, the final approach can be made via the Teach Miodhchuarta’.

This monument is thought to be one of the oldest structures at Tara, dating to 2700BC. Early Irish literature portrays this feature as the setting for each reigning High King’s feasts; in fact, a drawing from the Leabhar Glinne Dá Locha (the Book of Glendalough, dating to the twelfth century but gathered from earlier sources) goes so far as to present a seating plan for the king and his guests.

Today, this feature is recognised as a ceremonial processional road by which the monuments on the hill top are approached, a pathway between the physical world and the Otherworld of Tara, between the present and the past. C. Newman specifically links it with the inauguration and burial of kings. He also draws comparisons with the Knockans of Teltown, and the Mucklaghs of Cruachan: they all slope downhill towards what was originally bogland, feature irregularly spaced gaps in their banks, and lack identifiable ditches from which the bank material was dug.

An excavation of the partially destroyed Knochans in 1997 by Waddell and O’Brien yielded unexpected results, revealing that major structural phases had occurred between AD640-780, and again in AD770-990. Newman claims this has implications for Teach Miodhchuarta and the Mucklaghs: they could be much later additions to the royal complexes than previously thought, suggesting that an early Medieval date ‘connect[s] it [Teach Miodhchuarta] far more definitively with the institution of early Medieval kingship of Tara than if it were already some thousands of years old’.

This, however, poses a problem: at the time when the Knockans were under Medieval renovation, Christian scribes were busy imagining Tara as the royal residence of High Kings, not as a ceremonial centre. If Teach Miodhchuarta was indeed constructed in the early Medieval period, as Newman suggests, then the scribes writing about Tara from the seventh century onwards would have witnessed its construction, or at least have been aware of it and its purpose as the processional way of kings, instead of describing it as a banqueting hall.

It is also possible, though, that the Church was attempting to rebrand Tara even whilst it was still in use, to secure their religious and political goals, such as promoting Christianity, and courting the patronage and favour of the ascending powerful Uí Néill family.

A study by P. O’Keeffe in 2001 for the National Roads Authority disagreed with O’Lochlainn and placed the hub of the five ancient roads quite firmly at Tara. He claimed the Slighe Assail connected Tara with Uisneach and Cruachan, that the Slighe Dála passed close to Dún Ailinne, that the Slighe Midhluachra connected Tara with Emain Macha ( I have stood on this road), and that the Slighe Mór only joined the Eisker Riada at Balinasloe.

This indicates that the pre-historic purpose of the road network was to connect the major ancient ritual sites, allowing the flow of communication between the authoritative bodies governing each one, perhaps explaining how they were all decommissioned at the same time.

However, as L. Doran notes, these roads were ‘not physical entities but rights of way with legal staus’, meaning that it is unlikely travellers would have been able to travel along them in chariots at great speed as depicted in the stories of the Tain, for example, where warriors traversed the distance between Emain Macha and Cruachain in less than a day.

The terrain would have had to have been modified to accommodate them. In the minds of the writers of these stories, however, such travel seemed perfectly feasible, suggesting that by the early Medieval period, when the stories were written, the rights of way had been superseded by roads which certainly were capable of supporting wheeled traffic and horses.

Whilst presenting a logical progression, Doran’s theories are based on O’Lochlainn’s model, and completely disregard the importance of Tara as the central hub of the road network, which the compilers of the annals and the Christian scribes of the early Medieval period were keen to point out.

This ancient road system continued to be of use throughout the Medieval period and beyond, as can be seen in the number of Anglo-Norman castles, mottes and settlements at fords and crossing places along the Slighe Mór and Slighe Assail. HC Lawlor in an earlier study traced the route of the Slighe Miluachra through Ulster by identifying river fords. Situating one’s castle at a fording point gave the owner strategic advantage, both militarily and commercially, in terms of controlling access to the river, an important artery of transport and communication, and also to the road.

We can see this at Clonmacnoise, an early Medieval ecclesiastical site located at the intersection of the River Shannon and the Slighe Mór, also known as the Pilgrim’s Way. The remains of a wooden bridge dating to the ninth century were discovered at the ford beside the monastery, making it, as Doran says, ‘the earliest known bridge in Ireland and also the largest free-standing wooden structure in early Medieval Ireland’. This bridge undoubtedly provided a means of control and revenue for the community of monks at Clonmacnoise.

So, whilst it seems that there is indeed enough archaeological and literary evidence to support the existence of some level of road network extending from the pre-historic era into medieval Ireland, scholars are divided on the exact routes and the location of the central hub, either Tara or Dublin.

Most are agreed, though, that they appear to connect the provincial ‘royal sites’, thus corresponding with early literatures, such as the Táin bo Cuailnge. These roads appear to have been developed during Medieval times from rights of way into physical road structures capable of supporting horses and wheeled transport, possibly to facilitate trade and commerce, but also to cope with the increased traffic of pilgrimage where the roads passed by major ecclesiastical sites.

The ‘royal site’ at the Hill of Tara also presents a sixth road, as archaeological evidence has facilitated the re-interpretation of the Teach Miodchuarta from a king’s banqueting hall into a ritual processional way by which the summit of the site may be accessed (I will be going into this in a bit more depth in a future post), and with which all the five great roads connect. Recent archaeological findings at the Knockans, a similar structure at Teltown, have challenged the early dating of this monument at Tara, but remain a somewhat controversial theory as yet unproven.

This post is adapted from an essay I submitted for my Irish Cultural Heritage studies, and was originally published on aliisaacstoryteller on July 2nd 2018.

Refs.