Saint Brigid’s existence as devout performer of domestic miracels hinges on servitude, not just of God, but also of humankind. This gendered stereotype is completely at odds with the stories of the goddess so beloved of the people. Yes, Brigid the Goddess was a healer and a devoted mother, but as the conduit between Danann and Fomori, she wielded great political power. She was also a blacksmith and a poet; to the monks these were male callings that did not confrom to their idealised version of a Christian woman. So began the evolution of Brigid.

What is Imbolc?

FEBRUARY 1st IS A SPECIAL DAY IN IRELAND; as of this year, 2023, it has officially been declared a national bank holiday, the first and only national public holiday in celebration of a woman in Ireland: Saint Brigid, granting her equal status with her peer, Saint Patrick.

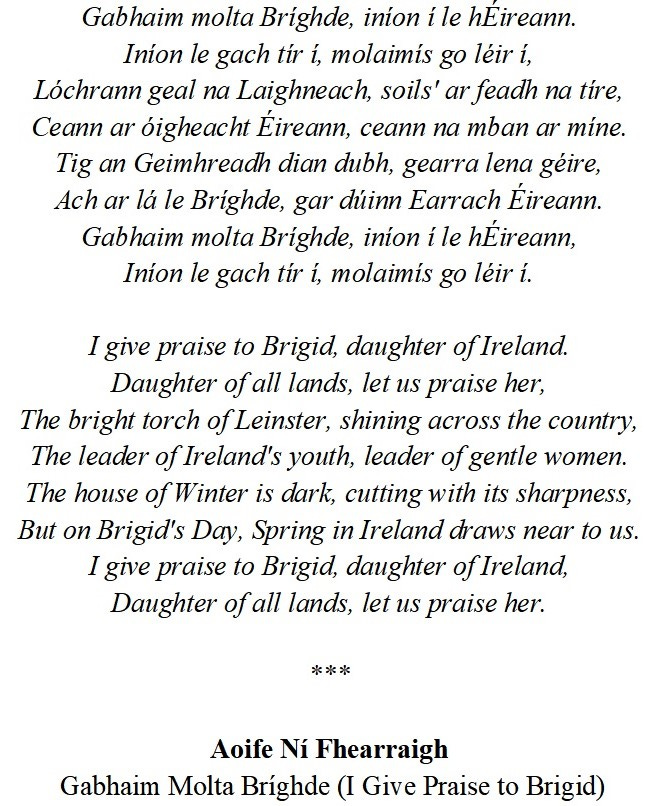

Falling half-way between the winter solstice and the spring equinox, and known on the Irish Celtic calendar as the festival of Imbolc, February 1st traditionally celebrates the beginning of Spring, and marks the feast day of Brigid.

Imbolc is one of four ancient Irish festivals, the others being Bealtaine, celebrated on May 1st; Lughnasadh on August 1st; and Samhain, held on November 1st. These major festivals were celebrated with the lighting of huge fires.

Despite its inception as the feast day of Brigid, the control of Imbolc rested in the hands of the Cailleach. According to folklore, it was on this day that the Cailleach was believed to gather her firewood for the rest of the winter. If she intended to make the winter long and hard, she would bless Imbolc with a bright sunny day enabling her to gather plenty of firewood to last her a long time. On the other hand, if Imbolc turned out to be a day of foul weather, it meant the Cailleach was asleep and winter was almost over.

I am not a native Irish speaker, unfortunately, so I must rely on the translations of others; a quick google search will offer many meanings of the word, Imbolc (not all of them by experts, it has to be said); nevertheless, my favourite explanation comes from the Old Irish imb-fholc, meaning ‘to thoroughly wash/ cleanse’. To me, this suggests the ritual cleansing and purification brought about through fire and smoke.

However, Imbolc is generally accepted to mean ‘in the belly’, with reference to the pregnancy of ewes. Indeed, the tenth-century manuscript known as Sanas Cormaic [Cormac’s Glossary]1 explains it as oimelc, or ‘ewe’s milk’. As such, Brigid has popularly become associated with the onset of the lambing season. ‘In the belly’ also suggests to me the mystical hidden work of gestation, both of animal and humankind in the womb, and the seeds under the earth. As a result, spring in many cultures seems to be associated with the generation of new life.

Sheep are not a native species of animal to Ireland; they are thought to have been introduced by Neolithic settlers some time after 4000 BC, so there would certainly have been sheep around in Brigid’s day. However, they don’t get much mention in Irish mythology, which is unusual; almost every other animal, wild or domestic, does.

The Danann were well known for their milk-white cattle; cattle were highly prized among our ancient ancestors, as the many stories of cattle raids, real and mythological, through the ages will attest. Queen Medb was famous for going to war over a bull, as told in the Táin Bó Cúailnge [Cattle Raid of Cooley], for example. Cows were also used as a measure of currency, as a measure of value, and as a measure of wealth.

In the ancient text known as the Lebor Gebála Érenn, Brigid was said to have kept two royal cattle called Fea and Feimhean, the Boar King known as Torc Triath, and Cirba, who was King of the wethers [castrated male sheep]. No lactating ewes are mentioned.

So it’s very interesting to note that in the tower on Glastonbury Tor, there is a carving which apparently depicts her milking not a sheep, but a cow.

Assimilation: Goddess & Saint

According to the Leabhar Gabhála Érenn [the Book of Invasions]2, Brigid was a member of the Tuatha de Danann, and the daughter of the Dagda. She married Bres, who was of Fomori/ Danann origin, with whom she had a son named Ruadán.

Brigid was credited with the gifts or skills of healing, of poetic inspiration, and metalworking. As with many of the Irish female deities [the Morrigan, (Badb-Anann-Macha; the Sisters of Sovereignty, Eriu-Fodhla-Banbha], she was a Triune Goddess, meaning she was one and three all at the same time. This triple aspect took the form of three sisters, all named Brigid, each sister representing one of her three gifts/ skills.

The name Brigid means ‘bright/ exalted one’, from the Sanskrit brahti, and is thought to refer to her association with fire and the sun. When she was born (at sunrise), a tower of flame was said to have extended from the top of her head to the heavens, giving her family home the appearance of being on fire. This is how the tenth-century text, Sanas Cormaic [Cormac’s Glossary] describes her:

Brighid, a poetess, daughter of the Dagda. She is the female sage, woman of wisdom, Brighid the Goddess whom poets venerated as very great and famous for her protecting care. She was therefore called ‘Goddess of the Poets’. Her sisters were Brighid the female physician, and Brighid the female smith; among all Irishmen, a goddess was called ‘Brighid’. Brighid is from breo-aigit or ‘fiery arrow’.

The fiery arrow is a fitting description for a poetess receiving knowledge through divine inspiration. It is also suggestive of the glowing white-hot iron she would have manipulated in the fire of the forge, a divine knowledge in itself, and the light she would have used as energy to conduct her spiritual healing.

Brigid’s husband, Bres, was an unpopular High King; he was mean and a tyrant, and was disliked by his subjects. So why did Brigid marry such a man? With her status and skills, she could have taken her pick of suitors. However, after the loss of an arm in battle, Nuada, as a disabled man, was no longer suitable to govern; a king was required to be flawless and physically perfect in order to bring prosperity and success to his people.

At the time, the Danann were being harassed by the Fomori; the Danann believed that as the son of a Fomori chieftain, the marriage of Bres with Brigid would appease the Fomori and bring peace. In other words, it was a political alliance. An arranged marriage. Brigid may have been given no choice, or she may have chosen to act in the best interests of her people.

Also, it is worth noting that Bres was apparently a bit of a hunk; his very name is said to mean ‘beautiful’. Brigid may well have been seduced by his physical charms. The texts don’t specify this; they do emphasise how handsome he is though, so I’m just speculating!

After seven years of Bres’s oppression and poor kingship, the Danann had had enough and opposed his rule, reinstating Nuada as their leader following the fitting of a silver prosthetic arm.

Furious at finding himself a king without a people, Bres enlisted the help of his Fomori relatives and attacked the Danann. During the battle, their son, Ruadán, entered the Danann camp on a mission to kill Goibniu, the Danann’s master-smith, but was himself killed in the attempt. Ruadán couldn’t possibly have been more than seven years old at this stage, although the text implies he was an adult, so this is quite a strange twist in the story, and a terrible tragedy for his mother. According to an ancient text known as Cath Maige Tuireadh3 [the Battle of Moytura], Brigid collapsed in grief over her son’s body, crying aloud her sorrow, and was thus said to have invented the act of keening [in Irish, caoine] for the dead.

It is thought that following Bres’s death, Brigid later remarried a man named Tuirean, and went on to have three more sons, Ichvar, Ichvarba and Brian. After that, her name seems to drop out of the stories.

Of course, our new bank holiday celebrates not a pagan goddess but a saint. However, it is commonly understood that Saint Brigid represents the adoption and Christianisation of a much loved pre-existing deity of the old religion that the Irish people refused to give up.

Early stories are rife with pagan imagery and symbolism, as their Christian writers attempted to draw communities into their churches. However, religious conversion wasn't their only aim. As always, the church was heavily involved in political meddling and the fight for power and riches; the manipulation of saintly reputation was key to their goals.

Texts which tell the stories of saints' lives are a 'genre' known in academic circles as hagiography. There are three existing hagiographies on Brigid, which are believed to date to the seventh or eighth centuries: Cogitosus's Vita Brigitae4, which is written in Latin, and also known as Vita II, and two anonymous texts: Vita I, which is also written in Latin, and the Bethu Brigte,5 which has some Latin, but is mostly written in Old Irish. I do not read Latin or Old Irish, so for the purposes of this post, I am relying on other scholar's interpretations.

Whilst most academics are understandably interested in which of the three texts is the oldest, perhaps, or which uses the most eloquent Latin, I am interested in what we can glean from them of Brigid as a woman, and in fact, whether she ever existed at all. Patrick's existence is unquestioned, because there are two letters still extant, the Confessio and the Epistola, which purport to have been written by him. We have no such 'evidence' of Brigid.

Brigid and Patrick were contemporaries in Ireland during the latter half of the fifth century AD. Kim McCone describes a line in an eighth-century poem, Ultán's Hymn, in which Brigid is 'one of the two pillars of sovereignty with pre-eminent Patrick'.6 The Liber Angeli, a text within Liber Ardmachanus [the Book of Armagh]7 also describes them as equals: 'between holy Patrick and Brigit, the pillars of the Irish, there was so much friendship of love that they had one heart and mind'; it goes on to describe an agreement in which Brigid ruled in her province, and Patrick in the east and west.

Cogitosus tells it somewhat differently; he describes Brigid as 'the head of almost all of the Irish churches with supremacy over all the monasteries of the Irish, and a paruchia [parish] which extended over the whole of Ireland reaching from sea to sea'.8 No mention of Patrick at all. Either way, it is clear that Brigid was a powerful woman, which is surprising given the patriarchal society and institution she was part of. And yet, although she was popular among the people, until now, it was Patrick who received all the glory, was appointed national saint of Ireland, and whose feast day became a public holiday. Why?

Brigid's sphere of influence covered Leinster, Munster, Connacht, and the territory of the Uí Néils, the ascending dynasty busy establishing its dominance at the time, and in whose disputes she was involved from time to time, despite being allied with the ruling Laigin, after whom Leinster is named.

Although she was the daughter of a Leinster chieftain, Dubhtach, Saint Brigid’s mother was a Christian slave girl named Brocca. Cogitosus, however, describes both parents as 'Christian and noble... belonging to the good and most wise sept of Echtech', and names her mother as Broicsech. Either way, Brigid was fostered out, as tradition of the time dictated.

Her foster father was a pagan druid, which rather suggests her own father may have also been pagan. As an infant, she failed to thrive, presumably because of her un-Christian upbringing, until she is fed the milk of a red-eared white cow, a creature with magical connotations in Irish myth.

This is surprising, as you would expect a baby to have been wet-nursed, and both Bethu Brigte and Vita I mention two Christian foster-mothers. These women are also described as virgins, so it may be that they were also nuns, in which case, they couldn't have functioned as wet-nurses. The fact that they milked the magical cow, however, extended their Christian virtue over the milk and made it safe for Brigid to drink.

As a child, Brigid was already performing miracles, but hers are of a very different nature to those performed by Patrick. Hers involved the practical and domestic, the churning of vast quantities of milk and butter which magically regenerated, no matter how much she gave away; the same with clothing; her mastery over animals both domestic and wild, her protection of the harvest, of turning water into ale, of changing stone into salt, and strange tales of healing: how she 'opened' the eyes of a blind man, restored the speech of girl who was dumb, and intriguingly, performed several abortions.

Patrick's miracles were more impressive (in a very macho kind of way): battles with demons, defying pagan kings, destroying pagan armies, smashing pagan idols with his crozier, driving snakes into the sea, raising men from the dead, clashes of magical powers with pagan druids, and such like.

Comparing the two, it becomes obvious why Brigid was so beloved of the populace. Respect for Patrick may well have come about through fear rather than love.

Brigid's miracles demonstrate a concern and compassion for the poor, the weak, the vulnerable, and the unfortunate, even at great risk to herself. Her willingness to give away food and clothing was so great, that according to the Bethu Brigte, it led to her father trying to sell her to Dúnlang, the King of Leinster.

The story goes that while the two men were bartering over her, she gives the King's jewelled sword to a beggar to sell so he could feed his family. Instead of being angry, the King realises her holiness and sets her free. She then goes on to found her monastery in Kildare, and the hagiographies describe five great journeys she undertakes in which she establishes her control over Ireland.

Cogitosus’s text is extremely sparse of detail. There is no chronology, no geography, no genealogy, no mention of her birth, a scant line concerning her death. Each miracle is given a bare paragraph, at best. This is hardly the life story of an important saint. One almost gets the impression that Brigid is not what is important in this text, that her story has been used to score some other message.

And of course, it has. You only have to look into what else was going on in the same period as the texts were written to see that there was a huge power struggle for supremacy going on between the church of Armagh, founded by Patrick, and the church of Kildare, founded by Brigid. The 'winner' would assume control overall, bringing with it land and riches. This was all tied up with the politics of the island at the time; aligning oneself with the dominant clan guaranteed success.

As a mascot, Brigid was a perfect choice for Kildare; the widespread worship of the pagan Goddess had imprinted her name in the landscape and in the hearts, minds, traditions and memories of the populace. Not only that, but according to McCone, there were many other Brigids with whom she may have been conflated; one text, the Comainmnigud nóem nÉrend, lists ten different St. Brigits and fourteen St. Brígs (a derivation of the name Brigid). Power in numbers, perhaps.

The strength of Cogitosus's text lies not in its portrayal of Brigid, but in the author’s manipulative skills; he made use of her reputation and standing in the community to safeguard the power of the church of Kildare. His prologue is a masterful piece of propaganda supporting Kildare's claim to the primacy, and as Sean Connolly says, his emphasis throughout rests on the theological values of faith and charity, Brigid's great strengths.

Although Cogitosus's agenda is so clearly and flagrantly politicised in his text, I really like it as an object in which the reader is able to connect with the author. We have his name, he makes sure of that. And whilst he is so self-deprecating of his own skills as a writer, it is obvious that he is really rather proud of himself and his abilities, and comes across as amusingly pompous.

But do we get a sense of the real woman behind the façade of Brigid he presents? Not really, beyond that her supremacy was vast, and her faith was strong. The Bethu Brigte is more detailed, and sketches more of her life, but the first page which probably recounted her origins is missing, and it ends somewhat abruptly with a 'finit' at a mid-point in her story.

McCone believes that the main concern of both these texts is to demonstrate the extent of Brigid's paruchia and influence beyond the province of Leinster itself. In other words, they were written to support the church of Kildare's power, rather than to teach the remarkable life of a female saint.

So, with all this material supporting Brigid as head of the church of Kildare and therefore the rightful candidate for the primacy, still it was Armagh and Patrick who came out on top. They looked beyond the borders of their own province to the Kingship of Tara for support, to the powerful Uí Néills. As McCone succinctly puts it, 'Armagh and and the Tara kingship were in cahoots from... the middle of the seventh century'.

WISDOM

1.

“this greening does thaw at the edges, at least, of my own cold season”

Mark Doty, poet, memoirist

It is, without doubt, a hibernation of sorts, this retreat from the cold, from the dark, from this raw wind which breathes frost into my soul, glittering shards of ice-like inspiration into my mind which only melt away with the warmth of my blood. I grasp after them, but it is a half-hearted effort and I soon fall back into my winter torpor. I have shut down, anaesthetised by the chill. You could cut me and I wouldn’t feel it, abandon me and I wouldn’t feel that either.

When the monochrome of winter begins to recede, I am startled by the vibrant green of the grass. It was there all along, teaching me a lesson about survival and endurance, but I was oblivious. When the buttery-petalled primrose pokes its shy head above the earth, I am reminded of sunlight, and I feel myself begin to thaw. I run into Brigid’s arms, feel the heat of the fiery arrow in her heart, the fire of inspiration roaring in her mind, the flame of the forge leaping in her blood, and I am renewed. Shame on you, she tells me, for refusing the gifts the Cailleach has brought you. The thaw hurts, but it is nothing to the burn of her rebuke.

2.

“Spring is the time of plans and projects.”

Leo Tolstoy, author, soldier

It comes from outside of me, straight into my head, my hand, and I write it down. Or tap it onto a screen. I don’t think it through. Actually, that’s not true. I am slow, I deliberate over every word, and how it relates to the previous paragraph, and the one which follows. But only after the word appears. I make many plans, but they are over-ruled by the words. By those who give the words to me. And it is now, just before spring, that new plans and ideas come to me. They are not unfamiliar, though; they have been whirling in my consciousness throughout the darks of winter and night, from the end of summer until now. I want to clean my windows, paint my house, revisit my wardrobe, my home-making, and clear the clutter. I am restless. I want to pare everything back to the minimum and start anew, peel back the soft flesh of my body and replace it with lean spare muscle. I want to breathe deep and taste the air. I want… to feel. And so, I open a new fancy notebook, a blank screen on my laptop, and I begin, once again, to lay myself out on the page. I am my biggest project.

3.

“With the coming of Spring I am calm again.”

Gustav Mahler, composer, conductor

In my H A G years, there is no such thing as calmness. I have forgotten what calm is. At least, I recognise it when I see it: a lake lying flat like a mirror, a sky without clouds, blue as eyes, a shore without waves, a tree still as stone without the wind wrestling its branches. But I don’t know how calm feels. It is not the same as winter torpor, I think. That is dull. Heedless. And the spring itself is not calm; it brings the turmoil of the scairbhin, but that is a good wildness, it blows away the cobwebs of lethargy which still thread their way through us, stirs the blood, gets the heart pumping, makes us feel ALIVE! That is what I want, to feel ALIVE.

Not calm.

4.

“I have called on the Goddess and found her within myself”

Marion Zimmer Bradley, author

Is she, though? Because if she is, she’s buried deep.

This is what I have learned; that those things which are the hardest on us bring the greatest rewards but only if we lean into them and practice acceptance. I am no goddess: dumpy, middle-aged, greying, wrinkles, a landscape of raging hormones. But my H A G years have revealed that elements of Brigid and the Cailleach both reside within me. How can that be when they are so opposed? It would be easy to assume these two female entities are polar opposites, nemeses, antithetical beings, just like the holly king and the oak king battling every year for supremacy. I don’t see it that way. Both women are mothers. Both are sheltering life. Both are working together to support nature and the planet. Teamwork. Sisterhood. Safeguarding life on earth. Multiple and one, just like Gloria Anzaldua. Just like you and me.

5.

“The snow has not yet left the earth, but spring is already asking to enter your heart”

Anton Chekhov, author, playwright, physician

The seasons have slipped out of synchronicity with the calendar, with the temporality of this planet. I feel this in my bones. We have done this by abandoning them. By recasting ourselves as God. We have Science now, and we are master of it. We have made trash of our world; even animals don’t soil their nests. The snow has not yet come, but I have always felt its weight. Its power to distort and disguise whilst coating everything it touches with sugar. Its sweet power is compelling, and we are dazzled. Bent beneath this lethal glittering blanket, I think of long summer days, the kiss and sigh of warm air, of sunbeams dancing between playful leaves, meadows with long, swaying grasses alive with the hum and drone of bees, and wildflower-scented breezes, my skin the only barrier between me and everything else, not swaddled in layer upon layer.

One snowflake is harmless, but they come as a blizzard. It is surprising how quickly they transform the landscape, how completely they cover me, blot me out of reality. But Brigid is forging her season within me, and I am burning anew.

This short film was recorded inside Brigid’s Holy Well in Liscannor, where Brigid is known as ‘Muire na nGael’ (Mary of the Gaels - see photo above). The poem was written by Doireann Ní Ghríofa, poet and author of one of my favourite books, A Ghost in the Throat.

Lessons from Brigid

What interests me about the above discussion is how, in their recreation of Brigid as a saint, Medieval writers formed a woman who represented their Christian ideal of the perfect pious wife and mother: the image of domesticity, miraculously producing copious amounts of milk and butter from her cows, feeding and clothing and healing the multitude of her dependents, constantly serving others and prioritising their needs over her own whilst asking for nothing in return.

Her existence hinges on servitude, not just of God, but also of humankind. This is a gendered stereotype completely at odds with the stories of the goddess so beloved of the people. Yes, Brigid the Goddess was a healer and a devoted mother, but as the conduit between Danann and Fomori, she wielded great political power. She was also a blacksmith and a poet; to the monks these were male callings. And from about 1400 AD well into the early modern period, the work of women healers was demonised and suppressed across Europe as witchcraft, its wielders condemned, tortured, and burned alive. In this way, healing power was transferred into the hands of men and renamed medicine.

The modern Brigid we have inherited has a duality, not a triple aspect; she is a curious assimilation of pagan and Christian. Stripped of her callings, the raging heat of her forge has become a flame kept alight in a nunnery, representing the hearth which must never die. The hearth was once the heart of a home, breathed into life and nurtured through the night by the mistress of the house. Still a vital duty until relatively recently, but reduced in public stature to a domestic chore. With her powers of healing abducted by men, along with the Imbas of poetry, very much considered a male trade in Ireland as late as the mid-1970s, one wonders how Brigid’s cult survived.

In parts of Ireland, though, love for Brigid the Goddess endured. Just up the road in Bailieborough, people continued to venerate Brigid the Goddess well into the nineteenth century with a stone head which they hid from the local priest in a cairn. Unable to stamp out this un-Christian idolatry, the priest brought the head into his church, but eventually threw it into Roosky Lake.

You can read this curious story here on aliisaacstoryteller.

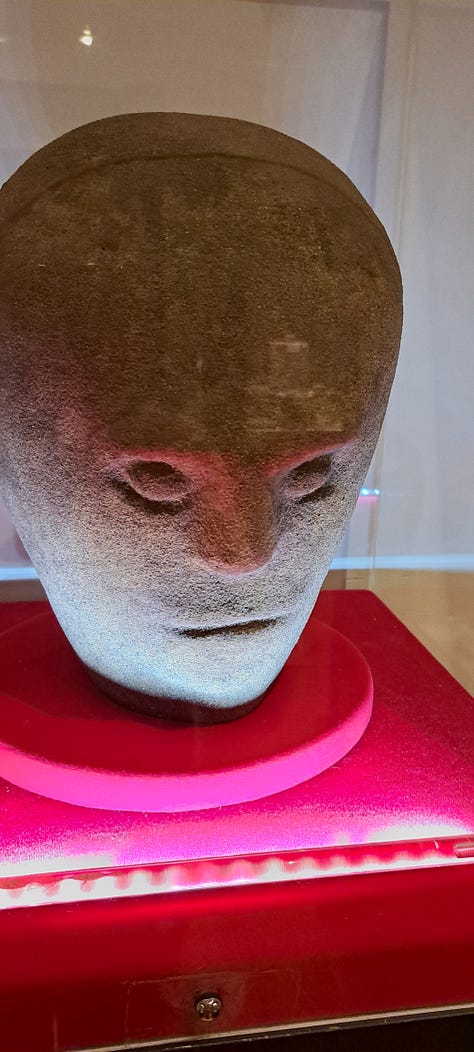

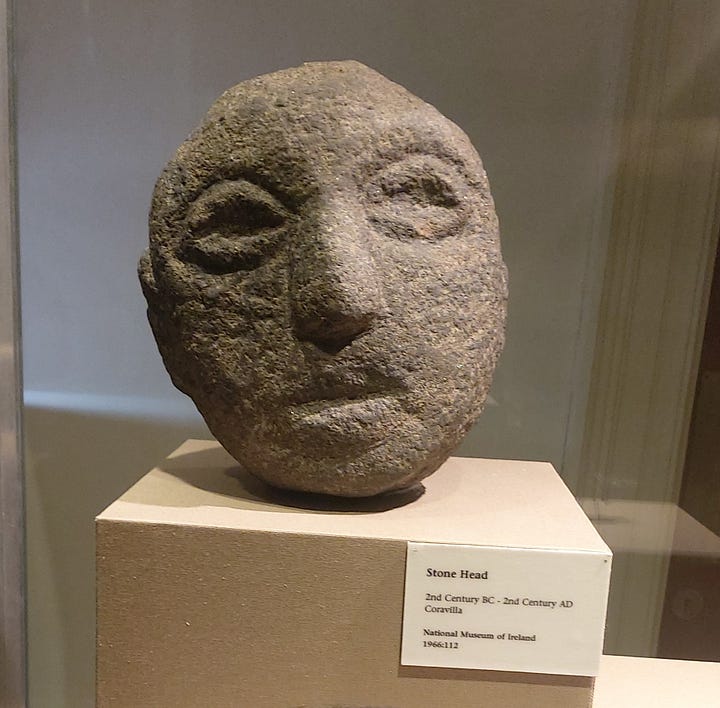

In Cavan, there is ample evidence of a cult of the head, and the museum in which I work hosts a number of stone heads. In fact, the enigmatic triple aspect Corleck head, found in Cavan but currently displayed in the National Museum in Dublin, is perhaps one of the most intriguing and mysterious examples of such a cult. Often associated with the three Gods of Art, I wonder instead, since the triple aspect is more common with female deities and Brigid, a triune Goddess, was known to be so venerated in the locality of its find, could this head actually be a representation of Brigid.

I have this vision of Brigid striding the landscape, as the Cailleach did in the season before her, wildflowers springing up in the grass where her feet have stepped, the floral scent of spring breezes drifting in her wake as she passes by. Mistress of forge and flame, she is the fiery arrow of divine inspiration and protector of poets, the healer. In Christian lore she is also the worker of domestic miracles, generous to the poor. In both guises, she is indomitable, and I instinctively sense her lessons will challenge.

With so many attributes, it is hard to know where to begin. But it is the Goddess rather than the saint with whom I feel most connection; as a writer and creator, I identify with her fiery arrow of poetic inspiration. My writing is not poetry, but it is part of me, a compulsion I cannot ignore. And this is very much tied in with my next lesson from Brigid: the Caoineadh.

Brigid grieved over the death of her son, Ruadán, as all mothers would do, but according to legend it was she who invented ‘the keen’ To keen is to mourn through song; it is the vocal lamentation of loss, and it is raw and powerful. The poet, Doirrean Ní Ghríofa was inspired to write her amazing book, A Ghost in the Throat, after falling in love with a well-known Irish keen, Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire, a lament for Art Ó Laoghaire composed by his wife, Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, who was the subject of Ní Ghríofa’s obsession. If you haven’t read it, and you are troubling yourself to read this newsletter, I suspect you will probably like it. (Confession: I wrote my Master’s thesis on it.)

I understand the Caoineadh not just as an outpouring of grief, but also as a way of letting go of what can no longer sustain us. This can be incredibly difficult, painful, and sometimes impossible to do. So, whilst my first lesson is to remove barriers to letting in Imbas, my second lesson is to let go of all things that are holding me back. This is a big task, and I have no doubt that it will open up worlds of pain and grief, but I believe it is crucial to moving on into my H A G years.

My third lesson involves healing. Since discovering my local 5km during lockdown, I observed, and became intrigued with the cycle of plant life growing in my local fields and hedges. I began to identify and research them, and found that nearly all have nutritional or medicinal value.

My search for a simpler natural life began some time ago; my daughter’s many health issues led me to question everything we have been told by the beauty, health and food industries, removing as many unnatural substances from our lives as possible. I began making my own natural skincare and cleaning products; I was convinced that in the past, our ancestors cooked up their own soaps and face creams in their kitchens as naturally as today we cook our foods. I was fascinated to read that Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses went to a pharmacy to order a face cream to be made for his wife, Molly. I don’t know what went into it, but clearly it wasn’t mass produced and pumped full of synthetic ingredients and toxic preservatives. My desire to incorporate herbal properties into my craft has already led to experimentation - more on that soon.

When I completed my Master’s thesis, one of my lecturers, who was my also my dissertation supervisor, gave me a beautiful handmade notebook, sustainably produced; he had created them as part of a project he was working on concerning trees. It was an unexpected gift, and I put it away for some at-that-time unidentified future use. This special little book will now record my herbalism adventure, and I will start with the first spring plant which arrives in February in profuse abundance in my locality: the humble wild primrose.

My three lessons from Brigid: to clear the way for Imbas, to learn how to let go of what is not serving me, and to follow my interest in herbalism.

What are your life-lessons for February? I’d love to hear about them in the comments.

Finally, you may have noticed something different about H A G… she has her own unique LOGO!

Isn’t it glorious? There is quite a lot of symbolism in this little sigil, but I’ll let you decide what that is, and what it means to you. I personally feel it is extremely powerful and represents much of what we have already discussed on this site since November. It was designed by my lovely friend and fellow creative, Séamus Draoigall. We had a productive business meeting (ahem… by that, what I actually mean is, a lovely lunch full of good food, chat and camaraderie), and this is how he interpreted my garbled list of logo desires. A true artist, professional, perceptive Saoi (man of wisdom). Check him out on the following internet spaces:

You can find Séamus on his website, deercún, and

Bethu Brigte, CELT.ucc.ie You can find translations by both Whitley Stokes and D. Ó hAodha here.

McCone, Kim. 'Brigit in the Seventh Century: A Saint with Three Lives?', Peritia vol.1, 1982, pp. 107-45.

Connolly, Sean, and Picard, J.M., 'Cogitosus's "Life of St Brigit" Content and Value', The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 117, 1987, pp. 5-27.

Other texts consulted: Sharpe, Richard. 'Vita S Brigitae: The Oldest Texts', Peritia, Vol 1, 1982, pp. 81-106

Wow, what an impressive account! Such a rich post. Thanks so much for writing.

Hi Ali. In Haiti there is another version of Brigit: Maman Brijit (Mother Brigitte), or Manman. She is considered to be the spouse of Bawon Samdi (Baron Samedi who is sometimes associated with St Expedite), and the mother of all gede (spirits). Cemeteries are considered sacred to her especially those in which the first burial was of a female. When female ancestral spirts are being petitioned first offerings of brandy, rum or black roosters are made at the foot of a tree consecrated to Brijit. She is believed to be of Caucasian appearance. In Born of Blood and Fire Richard Ward speculates that Brigitte could have been introduced to Haiti by Irish plantation workers or by Irish soldiers in the British army who occupied part of the island for 5 years in the late 18th century. Ward notes that "one of the animals associated with the Celtic Brigitte is the snake, and that, together with her associated element of fire, may have contributed to her adoption." In addition she is sometimes syncretized with both St Bride and Mary Magdalene.