Welcome and Thankyou

Lessons from November and December; Dunamase Castle and the women who owned it; my journey into herbalism with meadowsweet; Cailleach's Circle; your story; first Gathering

Hi Hag-Friends!

Firstly, thank you all so much for trusting in me and supporting H A G… it really means so much to me. And also means I have some work to do. I feel some trepidation; I want you to get value from the work I am doing, and that’s a big responsibility. So please don’t feel shy about making suggestions if there’s something you’d like me to cover here. And please do get involved; I love to get comments and hear your stories. Sometimes, walking the path of the Cailleach Project can feel a bit lonely, and yet I know there are many women going through similar experiences. Modern lifestyle has outlawed and isolated us so that we have become invisible even to ourselves. We need community, and I hope H A G serves as a starting point for those of us looking for a more meaningful way to walk our elder years. Let’s get to know each other in this safe space, let’s be here for each other.

So… let’s get started. And I’m moving forward here by looking back. I launched H A G in January, but my journey actually began in November 2022, when I reached a kind of personal crisis point. I shared this story in my last newsletter, so I won’t repeat it. If you haven’t read November’s newsletter, which was my first ever H A G newsletter, you can read it here. I tried to claw back some control in my life by turning to the Cailleach, and she in turn directed me to the Mórrígan.

November | Excursions into Darkness

The dark is guileless, innocent, a fact of nature, a wonder of the planet we live on. The dark of night should be embraced as part of our physical experience of being, for although it has no physical form itself, it still impacts on ours.

I realised I was afraid of the dark, but not just the darkness of night; I was afraid also of the darkness of winter, and my own inner darkness, the latter being the state of my own mental health. At that time, the effects of menopause made me feel like I was going crazy, my emotions were all over the place, and I was depressed one minute, anxious the next, and then euphoric before sliding back down again. As well, I was extremely forgetful, forgetting the end of my sentences, searching for key words that I knew I knew but where there was a blank in my brain. I was a real mess, and it was affecting my work at the museum as well as my personal life. With my own inner being sliding out of control as well as the dramatic physical changes taking over my body, my self-confidence, always a fickle thing at best, took a deep nose-dive. Something had to change, because I couldn’t bear being me anymore.

I’m not a religious person, so my journey with the Cailleach is not that of deity and devotee; it is more like teacher and student. I began reading about her, and I found focus for my scattered mind, and connection. I isolated my fears and went to meet them. I went into the darkness of the Mórrígan’s cave at Cruachan, deeper than any moonless night, descending beneath the weight of the earth, where I entrusted my safety to the women in front and behind me, to the ability of my body to navigate itself through confined spaces, over treacherous wet rock, through mud so thick you could imagine it would suck you under. I did not like confined spaces; I never even use the lift at work, so going into that cave was one of the scariest things I had ever done. I also went for walks at night around my local neighbourhood. I stood out under the stars on clear nights, feeling small and insignificant but still a part of this magnificent messy cosmos. I moved around my home without reaching for the light switch. I lit candles, creating little pools of flickering light I could move between and dissolve into. And all of these small things began to pierce my inner darkness, like the stars lighting up as dusk falls.

December: Surrendering to Winter

The Loughcrew cairns are described as being created by a giant hag or witch who dropped stones from her apron as she leapt from hilltop to hilltop in an attempt to wield some kind of spell or great magic. This folklore explains the creation of a regional geographical feature, and is one of many such local legends found across Ireland, indicating that the Cailleach is most likely an entity popularly associated with structuring the landscape.

November’s lessons merged with December’s, as the Cailleach stalked the land and Winter well and truly took hold. I wrote about how my dread of the dark half of the year arrived at the summer solstice, as the last of the summer flowers to appear bloomed and died. My solution to this anxiety came in my observation of the Celtic calendar. The fire festivals our ancestors celebrated divided the year up into short spaces of six or seven weeks. I learned that Lughnasa was followed very quickly by the autumn equinox and then came Samhain, then the mid-winter solstice when the days begin to lengthen, even if we can’t see it yet, then Imbolc which signifies the first day of spring, then the spring equinox, and finally we are back at Bealtaine, the start of summer. I could endure these short spells of winter; I enjoyed marking the end of each one and welcoming the next with the lighting of my own little fire, or even just a candle. Without any ceremony, these tiny quiet private rituals became a source of comfort and reflection.

I now had coping mechanisms to help me accept the length and darkness of winter, but I still had to face the challenge of the cold. I began to add cold showers to my morning ablutions, and to leave off my shoes when walking around the house so that my feet connected with the cold tiles. When I got out of bed in the mornings, I did not immediately reach for my cosy dressing gown but allowed my waking body to adjust. I switched off the central heating earlier and lit a fire. And gradually, the cold began to feel Ok, like it belonged, which of course it does, and that I could comfortably co-exist with it, instead of every year dreading and resisting and feeling thoroughly miserable and uncomfortable.

I know the temperatures we feel in Ireland are nothing like the winters experienced in other parts of the world; my preparations would probably seem laughable to those who have to live with truly ice-bound climes. But we all have to start somewhere, and these small new practices have been life-changing to me, and that’s why I’m sharing them here. You don’t have to go big and bold; start small and work up until you reach a level that makes a difference to you.

My tolerance of the cold was challenged at Bealtaine this year. I rose before dark to witness the rising sun that morning at Loughcrew. It was one of those sharp nights, the ground crisp with a hard frost. With friends old and new I went into the mound and waited for the dawn. My breath billowed in a cloud all around me, and my feet, planted firmly on the ground, acted like conduits, bringing the frost out of the earth and into my blood. It was very cold, I felt it, acknowledged it, accepted its embrace, but did not surrender. I did not stamp my feet and flap my arms or complain. I just allowed myself to be with it. And felt fine. I admit to a little smugness at how well I handled it. I was proud of myself, and that was my undoing. When I got back to the warmth of my home later that morning, I began shivering. Even the heat of a shower and the soft enveloping of my dressing gown could not stop the tremors. I reflected on my experiences and regretted my pride, made an apology to whoever was listening, and immediately, the shivering stopped.

It was the most bizarre experience, and a powerful lesson. Achievement should be celebrated, but with humility and gratitude, not self-serving pride. I learned about more than the cold that day.

The Women of Dunamase Castle

I have long found this castle and its history fascinating, probably because its stones are entwined so intricately with the lives of women. We are told in the historical record that women of the past were not so fortunate as we are today; we are led to believe that we’ve never had it so good, that the patriarchy has been good to us. It is true that women’s stories are generally missing from history, that they serve as a vague background upon which male glory and power is written in bold. Women are often nameless, described as ‘wife of’ or ‘mother of’ some male personage, and this is deliberate; it is the removal of identity, of individual agency, of personal power. It is a means of oppression. Histories are usually recorded after the event; it is therefore the bias of the writer, and/ or the writer’s culture, which permits this act of suppression. Historians and archaeologists today look back at the past and rewrite it through the lens of their own culture, and with the rise of patriarchal religion and society, this has led to the omission of the female from history. I feel it’s important to remember this when engaging with history; absence of evidence, Carl Sagan warns us, does not equal evidence of absence.

And so, when looking at a castle like Dunamase, still mighty in its current state of decay, many of us think first of the man who commanded its construction, the man who designed it, and the men who built it. Lets get that out of the way first, and move on to the more interesting stuff!

The structure we see now is the remains of an Anglo-Norman building erected in two stages; the inner keep which rises from the summit is thought to have been built c. 1200 AD by a Cambro - Norman military man named Meiler fitz Henry, grandson of Henry I of England, who was appointed Justiciar of Ireland c.1198. The outer fortifications were added later, around 1208-1210, by William Marshal, Lord of Leinster.1

All of the women I am now going to tell you about are connected by two things: the man, Diarmuid Mac Murchada, and Dunamase Castle, which passed through the female line until it fell into disuse and disrepair.

Derbforgaill

This castle is implicated in an event which dramatically changed the course of Ireland’s history. In 1152, when King of Leinster Diarmaid Mac Murchadha (Dermot MacMurrough) abducted Derbforgaill (Dervorgilla), the wife of his enemy, King of Breffni (County Cavan), Tigernán Ua Ruairc (Tiernan O'Rourke), he brought her to Dunamase Castle. We know that this event played a significant part in the subsequent Anglo - Norman invasion of Ireland.

Derbforgaill was 44 years old when she was abducted, and she brought all her cattle and possessions with her to Dunamase. According to Brehon law, this suggests a divorce rather than an abduction, which means she may well have been a willing ‘captive’. Was she escaping a brutal marriage? Was this more of an elopement than a kidnapping? It has been suggested that her paternal family were attempting to forge a new political alliance with the King via marriage.

The Annals of Tigernach record that a year later “The daughter of Murchadh Ó Maelseachnaill came again to Ó Ruairc by flight from Leinster” (T1153.5) 2, whilst The Annals of the Four Masters claim that “An army was led by Toirdhealbhach Ua Conchobhair, to Doire-an-ghabhlain, against Mac Murchadha, King of Leinster, and took away the daughter of Ua Maeleachlainn, with her cattle, from him, so that she was in the power of the men of Meath” (M1153.11). 3 So one source claims that she left her abductor and returned to her husband of her own free will, whilst the second claims that she was taken from Mac Murchada by an army led by the High King and returned to her family in Meath. It’s confusing, and sadly we cannot now know the truth, but it has been the source of delicious speculation across the centuries between then and now.

Derbforgaill thus occupies quite a position of power within the politics of the time. How much control she was able to exert, though, is unknown; however, according to Brehon law at the time, a woman had the right to agree or disagree to a marriage, and the right to divorce her husband, so it is quite possible that she at least played some part in her own destiny. She certainly managed her own wealth and financial affairs. Contemporary sources record that in 1157, she donated a selection of altar cloths, a gold chalice, and 60 ounces of gold to the Cistercian abbey of Mellifont during its consecration ceremony. She also built the Nuns' Church at Clonmacnoise in 1167. Twenty one years later, she retired to Clonmacnoise, where she died in 1193 at the grand old age of 85.

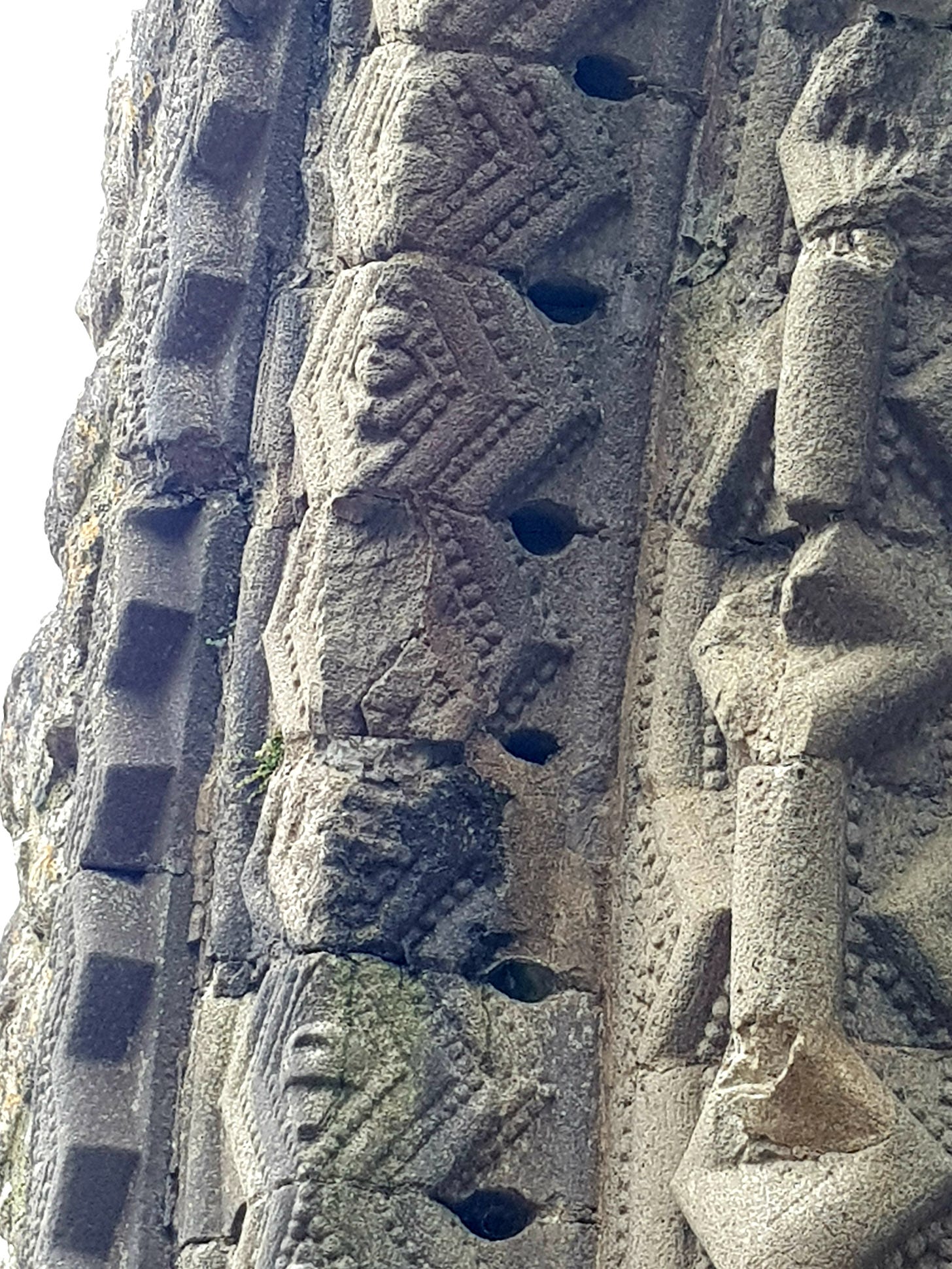

I just want to show you a detail carved into the entrance of the Nun’s Church, which most visitors probably miss, because you really have to look for it. It’s a detail I love, and I hope it tells us something about Derbforgaill herself. In the second stone from the top you can see a tiny Sheelanagig figure; it really is tiny, and you would pass beneath it to enter the church. It’s very unobtrusive, and nowhere nearly so explicit as most Sheelas. This is the earliest Sheelanagig figure to be found in Ireland. They are usually only found in association with church sites dating from the Anglo - Norman period onwards, so they are presumed to be of Christian origin, perhaps guarding against the sin of female lust. However, the Christians are known to have subsumed many pagan features and practices into their religion, so it is possible they could refer to earlier fertility goddesses. No one really knows for sure.

Aoife ní Mac Murchada

This is one of those moments when I find the study of history so frustrating. I want to bring you some meaningful information about this remarkable woman, but the historical record objectifies her as a mere political pawn in the power games of male wannabes and authoritarian leaders. She’s a card-board cut-out. A chattel passed from one man to another in exchange for wealth and power and personal gratification. I’m not in denial. I understand the way things worked. But she was also a human being, a real live person. As Doirrean Ní Ghríofa wrote in her extraordinary memoir, A Ghost in the Throat:

I want you to know that she was a female being.

I want you to know that she was a female, being.

I want you to know that she was.

That’s how I feel, because Aoife is so unreachable, and for the part that she played in Irish history, she shouldn’t be. Be that as it may, once she married Strongbow, once they settled into Dunamase castle, which was gifted to them by her father, once her father died and the kingship of Leinster passed to her husband through her, once she bore him heirs, she virtually dropped out of sight.

Aoife, daughter of an embittered provincial king, who used her as bait to lure the Anglo - Normans into his service, to fight his battles against Irishmen, who sold his country into slavery for personal gain, but never lived long enough to benefit from it.

Aoife, who at 17 years of age, educated in the ways of the Brehon law and Latin, went into the arms of a man twice her age, to please her father, who could never be pleased or sated. Aoife the battle-ready, sometimes known as Aoife Rua, fearless Irish she-warrior. She did what was required, she birthed two children, heirs to her husband, Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare, otherwise known by the epithet, Strongbow. She was absorbed by his legacy, consumed by time until all that remained was her name and a half-remembered legend.

Aoife, Queen of Leinster, Mistress of Dunamase, last princess of Ireland, fore-mother of generations of nobility and royalty across Europe, England, Scotland and Wales.

The date of her birth - forgotten, but thought to be around 1145. The date of her death - unknown, but thought to be around 1188. The place of her burial - Tintern Abbey, Wales, although no evidence of that remains today.

Aoife. I want you to know that she was.

Isabel de Clare

Isabel was the legitimate daughter of Aoife Mac Murchada and Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare. Upon his death in 1176, Isabel’s younger brother, Gilbert, became the chief beneficiary of his father’s will. He died in 1185, leaving Isabel a very wealthy heiress at the tender age of 13 to an estate which included lands in Leinster, Wales, England and Normandy. At this point, the Crown took her estate into safekeeping, and as a ward of King Henry II, Isabel was sent to live in the Tower of London under the protection of Ranulf de Glanville, Justiciar of England. There she remained until 1189, when at the age of 17 she was given by the King in marriage to William Marshall.

Although he came from a respectable family, William was just a professional soldier who had served in the Crusades and won the King’s favour through his tactical and political shrewdness; his union with Isabel served to considerably elevate his status. It seems that their marriage was a long and harmonious one, though, producing 10 children, 5 sons and 5 daughters.

William spent much of his time in England, serving as Lord Marshall to the various English kings, leaving Isabel in Ireland to rule over their lands in Leinster. Educated in French, Irish and Latin, she proved herself more than capable of the task, displaying a “keen sense of reality” in all her undertakings, and obviously earning trust and loyalty by providing a level of “advice and consent [that] was both needed and sought”. 4 Determined to consolidate her family’s power, Isabel worked hard to develop her lands, in particular constructing a deep water port in the borough of New Ross, whilst punishing her enemies, and forging close ties with her supporters through rewards such as land grants. When rebel barons used her husband’s absence as an opportunity to attack, she successfully led a campaign to defeat them.

When William took ill in early 1219, he left his family and joined the Templars, where he died some months later. His will made his two oldest sons his inheritors, however Isabel maintained control of her own estate. During the period of her widowhood, Isabel was very active in consolidating control of her inheritances, petitioning the Pope and King Philip of France for the speedy completion of all necessary administration. She also managed to cement profitable family alliances through the marriages of some of her children.

Despite this, Isabel’s widowhood was short: she died only 10 months after her husband, and was buried at Tintern Abbey in Wales beside her mother, Aoife. However, that is not the end of her story. In the graveyard of St. Mary’s Church in New Ross, which Isabel herself had commissioned, there is a cenotaph bearing the inscription “Isabel Laegn”, meaning “Isabel of Leinster”; according to local legend, beneath this monument is where her heart lies buried, uniting her in death with the land she loved so well.

Eva Marshall

Eva… poor Eva. Daughter of William Marshall and Isabel de Clare, grand-daughter of Strongbow and Aoife. Around 1221, she was married to Lord of Abergavenny, William de Braose, a man much hated by his Welsh kinsmen, who named him Gwilym Ddu (Black William). She had to endure the shame brought upon her by a husband executed by hanging for adultery with Joan, Lady of Wales, wife of Llywelyn the Great, Prince of Wales. Shortly after, one of Eva’s four daughters was married to the Prince’s son.

Seems to me that Eva had a lucky escape. Furthermore, she inherited all of her husband’s lands and property in her own right, to complement her own inheritance from her own parents. She died in 1246 aged 43.

Maud de Braose

Maud, sometimes known as Matilda, was the second daughter of Eva Marshall and William de Braose. Born in 1224, she was only 6 years old when her father was hanged for adultery. In her early 20s, she was married to Roger Mortimer, 1st Baron of Wigmore. Her toyboy by seven years, they had been betrothed since they were children. They went on to have six children together.

Maud was said to have been as intelligent as she was beautiful. She managed all her husband’s estates and business affairs with great flair.5 She was also quite politically motivated, becoming involved in the Second Barons war and plotting the successful rescue of Prince Edward (who later became King Edward I) after he had been captured by Simon de Montfort.

Widowed in 1228, Maud died in 1301 aged 77, and was buried at Wigmore Abbey.

Meadowsweet - My Sweet Summer Love Affair

For some years now I have been drawn to two particular wild plants; the first is yellow gorse, and the second is meadowsweet. In my journey towards Hag-dom, I feel drawn to working more closely with these two plant allies to see what I can learn from them. I have planted a lot of gorse around my garden, because although it grows all over Cavan, there is not much of it in my neighbourhood. The meadowsweet, though, grows in profusion, and particularly this year, although, as I mention in the film, since it came into flower, it has been so wet that I have been unable to harvest much of it.

Meadowsweet tends to be overlooked and under-appreciated, I think, probably because it falls under the shadow of some of its more showier friends, such as the rosebay willowherb, the foxglove, and the ragwort, which are all blooming at the same time, and tend to draw the eye due to their size and vibrant colour. Perhaps that’s why I like it, because it is the under-dog of the summer wild flowers.

Meadowsweet is native to Ireland. Its blossom is a creamy white, fluffy-looking and somewhat raggedy flower. It usually presents on reddish stalks. It’s leaves are very distinctive, pinnate and dark green on top, lighter underneath. It’s Irish name is Airgead Luachra, and it is part of the rosacea family, along with the dog-rose and blackthorn.

In folk medicine, meadowsweet was traditionally used to fight pain and inflammation. In the nineteenth century, it was discovered to contain salycilic acid, which is also found in willow bark. Salicylic acid is a disinfectant which has strong pain-killing and anti-inflammatory properties, and is the main constituent in the drug we know today as aspirin. In fact, the drug’s name derives from meadowsweet, “'a' for acetyl and '–spirin' for Spirea, the original botanical name for Meadowsweet”. 6

Last summer, for the first time, I collected meadowsweet flowers and infused them in oil, which I then used in my facial skincare throughout the winter. Every morning, its beautiful scent would uplift me with a blast of summer and a feeling of wellbeing, and the condition of my skin improved significantly. I am doing this again this year. This is how I do it.

Collect your flower heads. Make sure to collect them on a dry sunny day. Pick flower heads that are open but still have some buds. If they are all fully open, they won’t have as much scent. Pick sustainably, ie only take what you need, plucking one or two flower heads from each group of plants, leaving plenty behind for other creatures to enjoy and for the plant to regenerate itself.

At home, spread out the blossoms on a tray. Allow any little beasties to escape. I have seen some online sources recommending you give the flowers a good shake to dislodge any bugs. Don’t do this; you will lose the pollen, and that’s where all the goodness and scent is stored. If any bugs end up in your oil, you can remove them later.

Put the flowers into a glass jar, and cover with your oil of choice. You could use sweet almond oil, sunflower oil, grapeseed oil, any oil which is neutral (has no scent of its own) and is non-comedogenic (it won’t clog your pores). Make sure the flowers are completely submerged in the oil; any parts sticking out of the oil will begin to decompose, and won’t smell too good.

Leave on a sunny window sill for about six weeks. You can give it a gentle swirl every now and again, and remove the lid to check the scent is developing.

When the oil is ready, remove the flowers and strain the oil through a sieve lined with a piece of muslin. Store in a dark glass jar to preserve the scent. You can use as is, or dilute with other oils.

Last year, I used it as a cleanser. I massaged it into my skin, let it soak in for a few minutes, then removed the excess with a hot damp face-cloth. It always left me feeling amazing! This year, I want to incorporate it into a skin balm.

Meadowsweet is safe to consume as a food or drink too. Here are some ideas you can try:

Meadowsweet tea - use fresh, or dried.

I will be trying all of the above… providing the torrential rain eases up before the flowers go to seed!

A date for your diaries

I am proposing that we meet for our first Gathering at Loughcrew in September on one of the following two dates: either Saturday 16th or Saturday 30th. I hope this will give those of you who are within travelling distance plenty of time to make your arrangements. Please take a moment to let me know which date would suit you best; I want to be as accommodating of your needs as I can. I can’t wait to meet you guys! Btw there is no pressure to be part of the Gathering, but if you can, it would be wonderful, so why not?

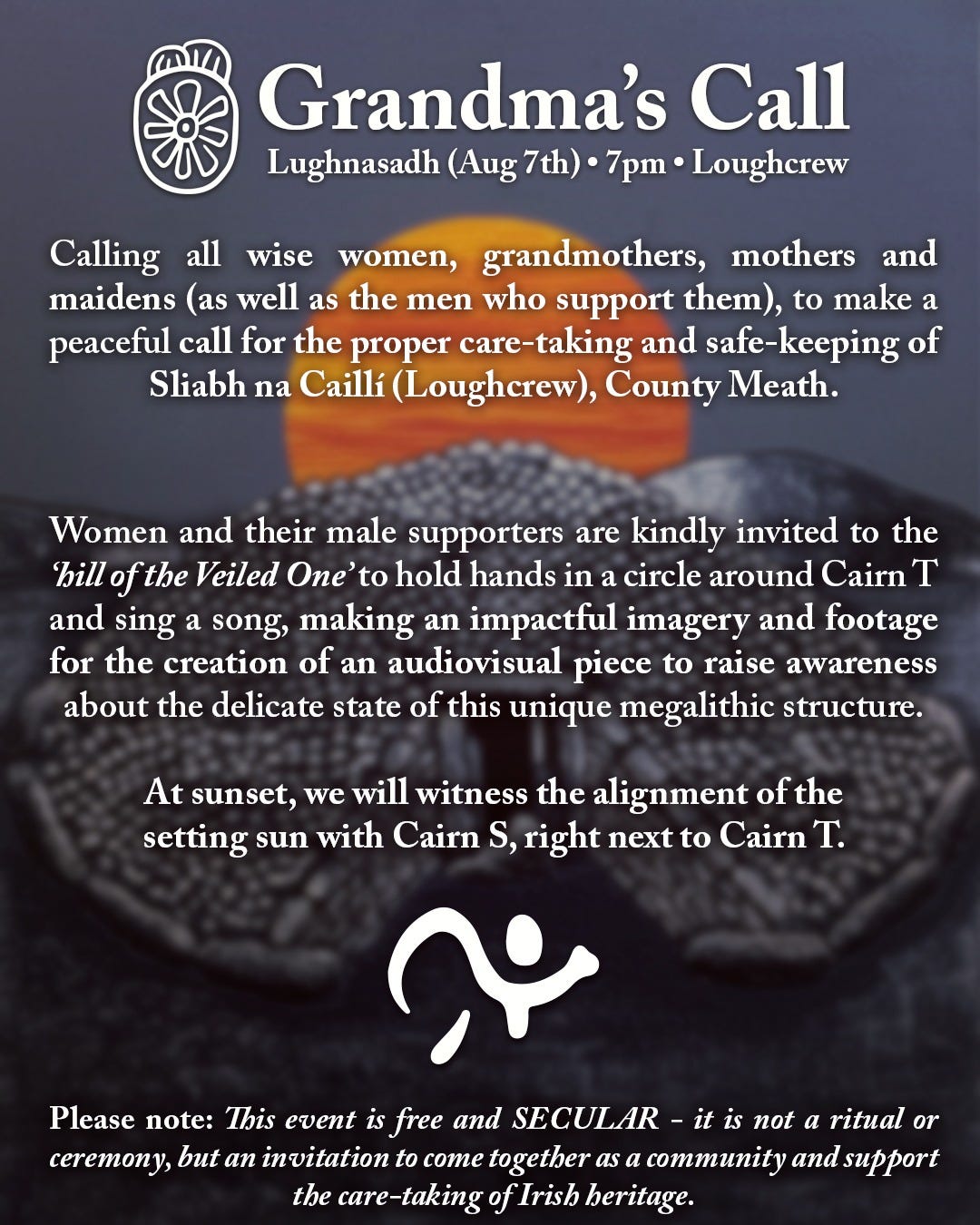

Calling all Rebel Cailleachs!

Just a reminder about this, happening soon:

I hope you will give this event your full support, after all, us Cailleach’s have to stick together! Seriously, it would be great to meet some of you there, if possible. And if you can’t be there in person, please send all your positive vibes and intentions… we want to see Cairn T restored to its full glory and open again. I will try and post pictures and short video clips to my Insta on the night, for those who can’t be there in person.

For more details see my last newsletter:

An Invitation from the Cailleach

The first time I visited Loughcrew, Carys was still small enough to be carried up and back down again in Conor’s arms. In the 16 years that have passed since then, I have returned many times to the H…

The Cailleach’s Circle

I will be enabling Substack’s Chat function this Friday 28th July 2023, which means we will be able to communicate directly with each other, kind of like having our own private social media platform! I’m really looking forward to this, it will be informal and fun! You will probably get an email notification when it goes live, which will give you all the details you need about how to access and use it, and then you can dive right in, if you want to… look out for it, it will be called The Cailleach’s Circle. I don’t know where in the world you all are, so some of you might be sleeping, but that’s the beauty of social media, the Chat will still be available to you to respond to at a time that suits you. If you have the Substack app, you will be able to access it there. The Cailleach’s Circle is only available to you, the paid subscribers, so it is quite private, and I hope it will be the safe, supportive space I envision it to be. Can’t wait to meet you there!

Your Story

We all have one. I have recently shared some of mine with you. I’d like to hear yours, and I’m sure I’m not alone in that. We need to feel part of something, that what is happening to our bodies and emotions and minds as we age is normal, and that we can get through it safely, wise and well. If you have a platform of your own, share your links here so we can connect with you in your own space. If you don’t have your own platform, share your story in the comments, or email me by clicking return to this newsletter and I will feature your story in your own words here in the HAG - Wise newsletter.

Signing off now, my lovelies! Hope you have enjoyed this newsletter. Beanachtaí and grá mór always, Ali x

Mitchell, Linda Elizabeth. Portraits of Medieval Women: Family, Marriage, and Politics in England 1225–1350, Palgrave MacMillan, 2003, p. 45.

Wildflowers of Ireland. I also highly recommend Ireland’s Wild Plants: Myths, Legends, and Folklore by Niall Mac Coitir

I wish I could come to gatherings in Ireland, but I'm in San Francisco and travel isn't very feasible for me at the moment!

I love being a hag. :)