The quote in the title comes from one of Yeats’s poems, Crazy Jane Grown Old Looks at the Dancers, in which the observer watches a young couple dance together with great passion, and an element of violence. The refrain, repeated at the end of each stanza, implies there is danger in love. Or, I suspect, where we find danger, we will also find love.

Dens leonis (Latin), or dents de lion (French), is the name given to a very humble plant that we know better as the Dandelion. Its name means ‘teeth of the lion’ on account of its distinctive jagged leaves, and its cheery golden presence is often a prolific imprint of colour upon the landscape in which I live.

Dandelion, or Caisearbhán in Irish, is often one of the first flowers to appear in spring, and so is associated with Brigid, although the first wild flower to raise its fragile head in my area this year was a brave and foolhardy daisy (Nóinín in Irish) on a particularly cold windy day in mid-January.

In Irish and Scottish Gaelic, the dandelion is sometimes called Bearnán Bríde, meaning ‘the indented one of Brigid’, again referring to the shape of the leaves. Scottish lore linked Brigid to this plant by claiming its ‘milky sap nourished the early lamb' in the same way that Brigid protected them. 1 In order to protect a milk yield from witches, a Scottish Highlands tradition involved placing a hoop woven from dandelion, milkwort, butterwort and marigold beneath the milk vessels. 2

The dandelion is a member of the daisy family. Like babies and small children are drawn to the colour yellow, I am always drawn to yellow flowers, hence my long obssession with gorse, for example. And primrose, which is really coming into its own right now.

The dandelion, however, is nothing but a nasty weed that infiltrates one’s carefully curated lawn, right?

Wrong. There is no such thing as a weed. The dandelion is a wild plant, and deserves our respect. It is a native of Ireland, which means it grows where it belongs, and I welcome it to my little patch of wild land for its bright beauty, and its generosity; the dandelion really is a plant that keeps on giving.

Dandelion - Its History, Medicinal & Nutritional Uses

This sunshine-flowered plant has been used for centuries throughout Europe for medicinal as well as nutritional purposes. Historically, it was known as a diuretic, leading to common names such as ‘piss-the-bed’, and children were warned not to even pick it for risk of the plants milky sap being absorbed through the skin; medically, this property was considered helpful in ‘promoting the flow of urine and thus assisting kidney and associated troubles’, according to Niall mac Coitir. 3 It was also used to cure issues with the liver, bile production, jaundice, upset stomach, and rheumatism, and even tubercolosis.

According to Christine Iverson, dandelion roots were so sought after for their medicinal properties that there was a thriving industry of ‘root-diggers’ which lasted well into the 1930s. 4 This benefitted local farmers, as the diggers helped remove unwanted ‘weeds’ from their fields. The roots were collected and then sent to London by train for processing. Diggers would earn 3 pence per pound (454g) of washed roots, and 1 penny per pound of unwashed roots.

Today, dandelion has been found to be high in potassium and vitamins A, B, C and D, which are known to have a cleansing effect on blood, and a stimulating effect on the liver. Dandelion buds can be collected early in the spring for making capers. The early greens are perfect for adding to soups, smoothies or turning them into a dandelion tea. Young leaves can be added to salads for their fiery, bitter taste, and can be made into a pesto. As the season progresses, dandelion roots and flowers can be added into dandelion fritters, honey, or jelly. 5

Flowerheads are typically used to make a very potent dandelion wine, sung about so beautifully and mournfully by Ron Sexsmith, a song which echoes Yeats’s theme of danger in love (I first heard Ron Sexsmith sing the day we recieved the news that our daughter Carys might never be born alive, this song in particular is bittersweet to me). Dandelion flowers can also be used in beer-making, added to cordials, and used to flavour vodka.

When I was a child, my favourite fizzy drink was Dandelion and Burdock. I doubt if either of these plants ever made it into that particular beverage, but it originates from a medieval brew once made with mead and fermented dandelion and burdock roots. 6

In terms of wellbeing, according to Vladka, dandelion heads are moisturizing and soothing for the skin, great in the form of oils or salves for relieving pain and healing dry or cracked hands. They have mild pain-relieving properties that may ease sore muscles or achy joints, especially for people with arthritis. 7

The Dandelion - Folklore Fun

As well as curative properties, the dandelion could be a source of fun and games for the young. Who hasn’t, as a child, blown away the seeds from a puffy dandelion clock in summer, watching them dissipate in the breeze, and taught their children and/ or grandchildren to do the same? I always imagined those little flyaway seeds as tiny fairies, and Sandra Lawrence describes how the seeds “were thought to be fairies, and blowing on the clocks released the little folk from their capture”, and she advises to always make a wish before making a puff. 8 Or, you could catch the ‘fairy’ and “hold it to ransom” as you made your wish, and then release it.

I never knew that the number of breaths it took to blow away all the seeds was meant to be an indication of the time, hence the childhood name of ‘dandelion clocks’.

According to mac Coitir, the number of breaths enabled the lovelorn to divine the number of years before getting married. I was taught that pulling off petals from any flower, or twisting the stalk from an apple, whilst saying “love me”, “love me not” would indicate whether your love would be returned or unrequited, but Mac Coitir claims it could also be applied to blowing seeds from a dandelion clock. Christine Iverson writes that if you blow off all the seeds in one go, you would be loved with a passion, but if some seeds remained your lover had doubts; if most remained, she advised looking elsewhere for love! 9

Dian Cecht’s Porridge

In Irish mythology, Dian Cecht was the physician who replaced King Nuada’s severed arm with a fully functioning arm made of silver, an early bionic prototype, if you like, or at least a functioning prosthetic. He also knew the secret of the holy well, transforming naturally formed pools of water into places of healing that could revive battle-weary warriors, and even return the dead to life. Along with his sons and daughter, he did this through enchantments and the use of herbs.

Dian Cecht’s Porridge was a cure that was used in ancient Ireland for fourteen different stomach disorders, as well as worms, sore throats and colds. I had heard of this magical concoction, but never knew what was in it. According to Mac Coitir, it contains dandelions, hazel buds, chickweed, wood sorrel, and oatmeal. 10 How effective it was, he doesn’t say, and according to myth, it was his daughter, Airmid, who was the herbalist in the family.

Dian Cecht’s healing prowess, however, lives on in the numerous holy wells around the country, all of them attributed with cures for specific ailments. Nowadays, they are associated with saints, most prolifically Patrick and Brigid, but it is generally believed that the use and powers of holy wells extend much further back in time than christianity.

In next week’s post, I will be bringing you two dandelion recipes you can try for yourself.

Dandelions and Hope

I started off this newsletter writing about dandelions and their association with love and danger, and in a roundabout way, we are coming back to this juxtaposition.

On the 10th of January, I saw my first daisy. I wasn’t expecting to see any wild flowers at that time of year. There were snowdrops, but they were planted by a neighbour. I was, at that time, and often since, feeling despair over the two wars and the climate crisis. That tiny little flower gave me a jolt of joy. It told me a lot about survival, and finding hope and happiness.

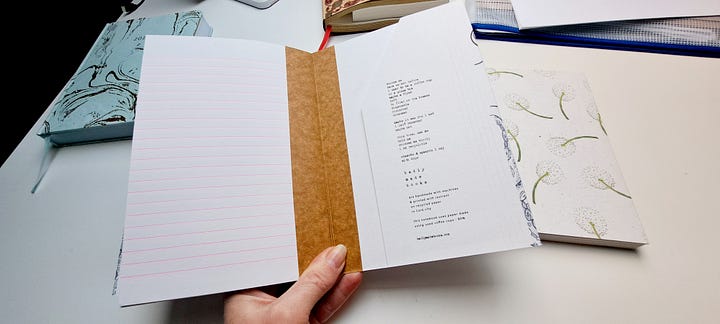

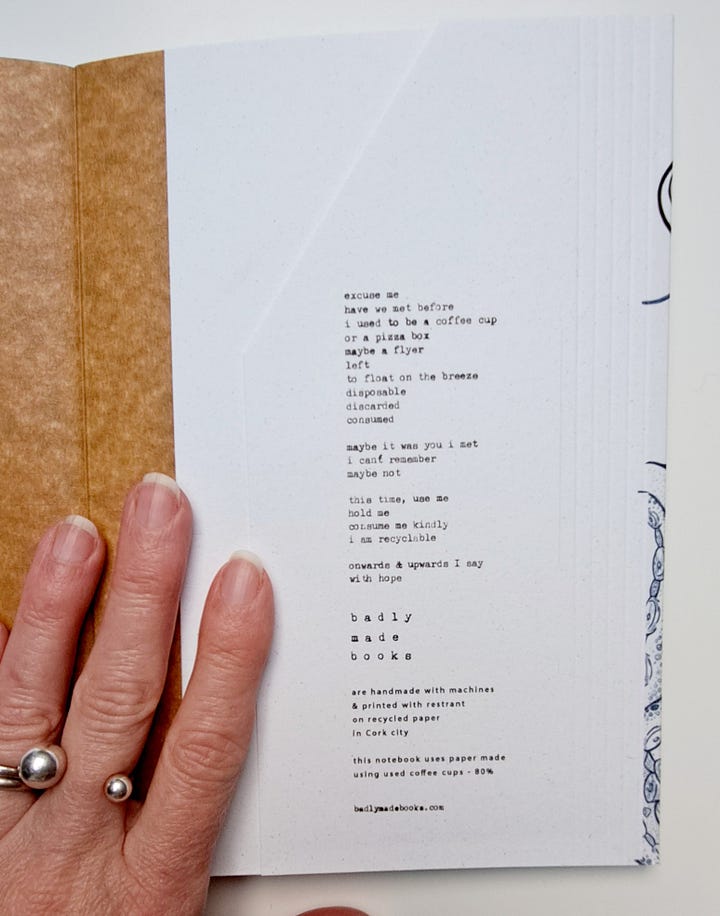

The next day, my two notebooks from Badly Made Books arrived, my litte Christmas pressie to me. The one with waves on the cover is to write all my notes in for a YA trilogy I am working on that is based on Irish mythology and climate change. The second, with the dandelion clocks on the cover, is my little Book of Gratitude. Their arrival also brought me a little jolt of joy. But I had picked the dandelion notebook without much thought other than I liked its simplicity.

As I began writing in it, I found myself thinking more about that versatile little plant depicted on the cover. I knew about the dandelion’s multiple culinary and medical uses. I knew also that every part of it was edible. I knew that its stems and leaves could be dried and used to make cordage and for weaving. I had watched chaffinches eating its seeds from my overgrown lawn in the summer. I had admired its gorgeous reliable blast of uplifting colour year after year. And yet, somehow, its true value had slipped beneath my radar. I had never fully appreciated it.

I did a bit of digging (metaphorically speaking) and I learned that the dandelion is regarded as a symbol of hope, healing, and resilience in many cultures around the world.

The cheery bright face this little flower lifts to the sky is a reminder of that great golden orb, the sun. The sun brings warmth and regeneration in spring, heating the earth and air so that germination can take place, and plants can grow. This abundance brings forth new animal life, so that all aspects of the food chain and life cycle are nourished and replenished. The dandelion is our first sign that this transformation has begun. It is therefore a powerful emblem of hope.

In the summer, the yellow flower gives way to a white puffy ball of minute seeds so small and light they float on the breeze. They drift away to begin a new life elsewhere. The dandelion is thus a symbol of change, transformation, and new beginnings.

It thrives in profusion, anywhere and everywhere, poor soil or not, even in the smallest crack of a city pavement, demonstrating strength, courage, adaptability and resilience.

The dandelion freely gives away so much of itself: it nourishes our bodies, brings us healing, provides materials we can work into useful tools, remind us of the beauty and power of nature all around us. It clearly has many lessons to teach us beyond its practical applications.

If all of that isn’t love, then what is?

Little signs of hope, everywhere

And what of the danger?

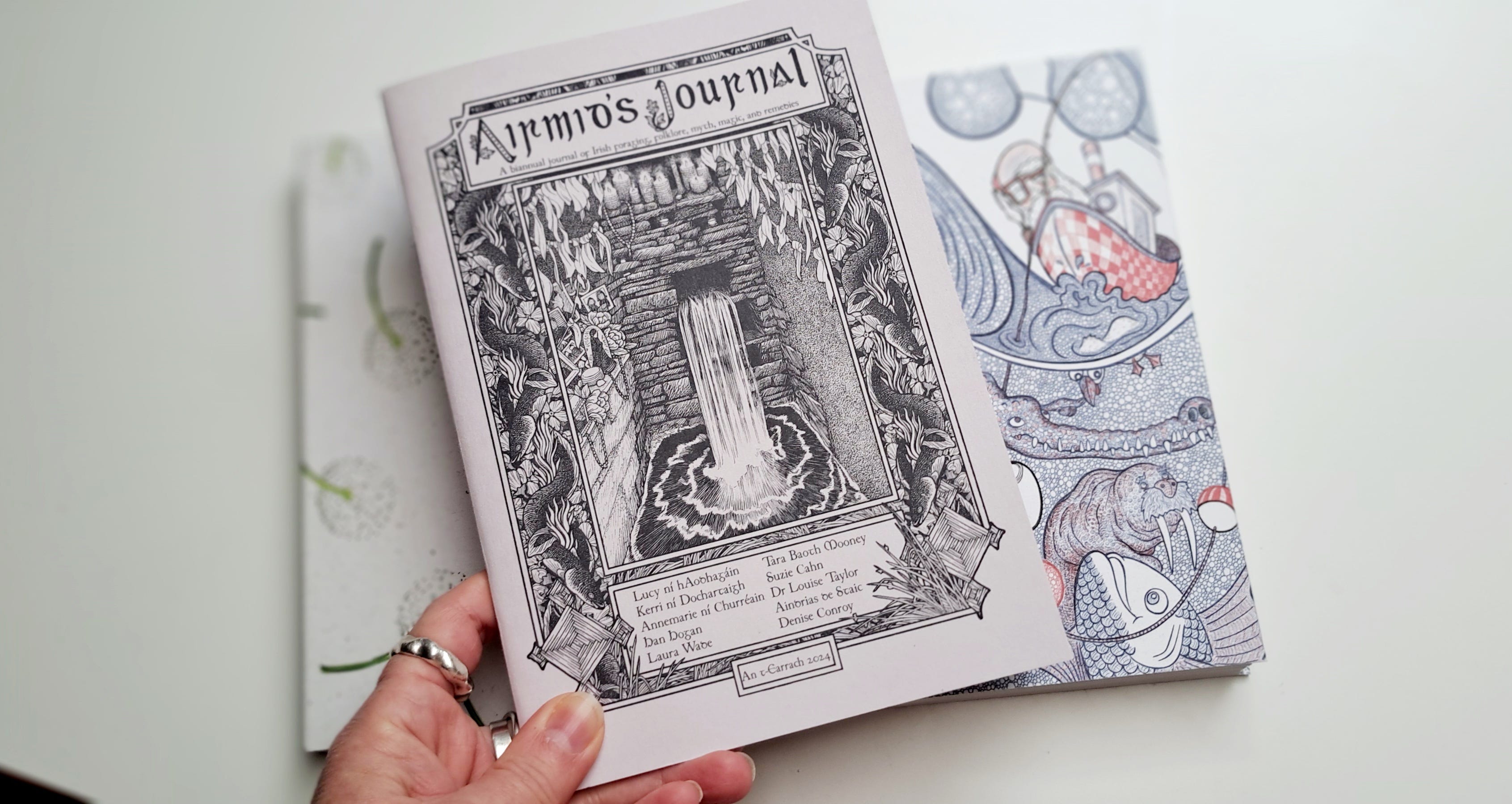

Last weekend, I was fortunate enough to attend the launch of the second edition of Airmid’s Journal with my friend, Jenni. It was a beautiful day, organised and hosted by Lucy ní hAogháin, of Wild Awake, and held in The Common Knowledge Centre in Co. Clare . Under a blue sky, bathed in warm sunshine, we took part in various activities with learned leaders. Jenni went off with Lucy to learn how to tan eel skins, I joined a masterclass with author Kerri ní Dochertaigh (Thin Places, Cacophany of Bones) on Writing through Emergency.

I listened to Kerri describe all the world events in 2019 which inspired her to write her book, and I began to feel emotion welling up, and there was nothing that I could do to stop it. That year, I had written my own book, in which I not only bared my soul but addressed issues I felt were devalued or ignored in society, such as disability, mothering, female aging, and bodies, especially female bodies and disabled bodies. 2019 was also the year that Doireann Ní Ghríofa wrote her stunning book, A Ghost in the Throat. Three important-to-me books all born in the same year. What an honour to be writing in the company of such authors, even if I didn’t know it at the time.

Anyway, when she finished speaking, Kerri invited all of us writers at the table to say something, and the first person she turned to was me. I’m afraid to say, in front of strangers, something in me cracked, and a flood of words came out. I said far more than I intended. But in doing so, I realised that I was suffering from grief. For the people of Ukraine. For the people of Palestine. For the planet, which we continue to damage, and all life on earth, which is suffering, and for my children’s futures. Part of that grief was helplessness; that’s where the danger lies.

Kerri then asked us to write a short piece about a personal emergency we had experienced. Mine involved saving my three-year-old from choking on a marble. And I realised that my grief stemmed from mothering; mothers protect, and they are fierce in that. I could protect my children, but I couldn’t protect the other wider things I cared so much for, like a peoples’ sovereignty, peace and safety, or the future of the planet. It’s just not within my power to do that. And on a very deep level, that caused me grief that I couldn’t even articulate.

I wrote everything down in my Dandelion notebook. My little Book of Gratitude. Those little dandelion clocks on the cover whispered of transformation, of tiny seeds floating away and lodging somewhere new, taking root and growing into something mighty; they hinted at strength and courage and determination. I realised something else. I still had hope, and hope is powerful. It’s where our creativity comes from, our urge to act. Kerri called it ‘the little bird’ within us, and finally, mine was beginning to stir.

In 2020, I learned what an avalanche of power gratitude is. Once you start to prectise it, you see things to give thanks for everywhere. They were always there, just you couldn’t see them. Hope is like that. Little signs of hope are everywhere. I’m seeing them, and I’m giving thanks for them. And this year, I’ll be taking my lessons from the dandelion.

What little sign of hope are you grateful for today?

Mac Coitir, Niall. Ireland’s Wild Plants - Myths, Legends, and Folklore, The Collins Press, Cork, 2018. (I love this book, my first go-to when I want to know something about plants)

Ibid.

Ibid.

Iverson, Christine. The Hedgerow Apothecary - Recipes, Remedies, and Rituals, Summersdale Publishers, London, 2019. (This is a beautiful book gifted me by Sarah, my sister-in-law.

If you are interested in this aspect of ancient brewing for health and all things witchy, you might like to read The Ale House Wives series on John Wilmot’s facinating Substack, Nature Folklore:

Vladka, see no 5. above.

Lawrence, Sandra. Witch’s Garden - Plants in Folklore, Magic and Traditional Medicine, Welbeck, London & Sydney, 2020.

Iverson, Christine. See no. 4 above.

Mac Coitir, Niall. See no.1 above.

What a stunning piece of writing. Thank you so much! It moved me so deeply. I too love dandelions, they cannot fail but bring a smile to my face, they've so much character and tenacity! I enjoyed hearing about your writing experience too, we are all grieving so much in this world right now, but still hope remains.

What a timely piece this post is! I have been noticing dandelions along the sidewalks where I walk this past week. They are such a bright spot in our gloomy days. My mother cooked us dandelion greens one night for dinner when we were kids. The dish did not go over well but it didn't stop her. She was always serving us wild greens. .