September | From Goddess to Grotesque?

An Exploration of the Sheela-na-gig as Cailleach

Sheela-na-gigs are virtually the only surviving element of one of the most important aspects of the native celtic tradition, [that is] its feminine orientation or belief in the ultimate deity as symbolised in the Cailleach or HAG, the goddess or the image of female spiritual power. 1

Introducing Sheela

During my recent work in the Cavan County Museum, I was surrounded by stone-carved Sheela-na-gigs. I didn’t find them vulgar; I liked their honesty. To me, they represented a confidence in their female form that I was struggling to find in mine. I see them as art, and as a conduit through which we might connect to the society of the past that made them. But I was confused; popularly interpreted as sacred incarnations of fertility, I felt quite strongly that these figures were something else entirely.

The Sheela-na-gig is a well-known icon in Ireland, commonly found above church entrances and windows. Some can also be seen in the walls of buildings such as castles and animal sheds, possibly relocated from their original installation.

The term ‘Sheela-na-gig’ first appeared in the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 1840–44, 2 with reference to a stone carving found lying on the ground in an old church-yard in Lavey, but which now resides in the Cavan County Museum.

I really enjoyed this brief yet thorough examination of the Sheela-na-gig phenomenon.

An Experiential Appraisal

You will no doubt have encountered the Neopagan concept of the female as maid - mother - crone, each aspect representing the cycle of her biological embodiment and/ or her sexual development. But historically, and mythologically, in Ireland, female identity and the roles of women are often (but not always) portrayed as diverse, rather than limited by their biology.

In Ireland, the triune goddess, for example, is usually depicted as three sisters representing a different aspect or facet of a particular figure. The Morrigan, for example, is the Goddess of war, yet she is composed of the sisters, Macha, a female warrior associated with ‘the heads of men slaughtered in battle’; Badb, who takes the form of a battle-crow and is a harbinger of death; and Nemain, who is credited with the frenzy and chaos of battle.

Other triune Goddesses are Eriu, Banba and Fódhla, who collectively represent Ireland’s sovereignty, and Brigid, three sisters who share one name and represent the fiery arrow of Imbas, or poetic inspiration, mastery of the forge, and healing.

As you can see, none of these Goddesses are characterised by the theory of maid - mother - crone, but by their skills. They are not defined solely by their fertility, sex, or gender.

When I look at a Sheela-na-gig, I don’t see the embodiment of fertility; I don’t see the nubile, fertile maid, or the ripe swelling mother. Unlike other fertility figures around the world, like the Venus of Willendorf, the Venus of Hohle Fels, or the Venus of Dolní Věstonice, the Sheela-na-gig does not have breasts or a large rounded belly or hourglass hips; the only physical feature which indicates her sex is her prominently displayed vulva. In fact, typically, the Sheela-na-gig has no breasts, appears to be quite scrawny, has lines inscribed on her torso which could represent ribs or tattoos, and rarely has hair. Were it not for the fact that she is generally depicted holding open her vagina with her hands, antiquarians and archaeologists, viewing the past through their patriarchal lens, would probably have assumed she was male.

The more time I spent with the Sheela-na-gigs, the more I began to see the Crone. The H A G.

WISDOMS

1.

The first appearance deceives many; the intelligence of few perceives what has been carefully hidden in the recesses of the mind.

Plato, Greek philosopher

I have been deceived by the Sheela. I was told she is a fertility goddess, and so that is what I looked for. But what is a fertility goddess? Where does she appear in our inheritance of stories? Many of the Sidhe women bear children. Does that make all of them fertility goddesses? I myself have borne three children; by that logic, all women must be fertility goddesses, incarnate in living flesh.

I have been deceived by the Sheela. I looked for the fertility goddess, but I didn’t see her. I thought she was a caricature of the female, reduced to vulgar display. I looked but I couldn’t see.

I have been deceived by the patriarchy. When I opened my mind, then I saw her. Not merely a fertility goddess, so narrow and singular a role, but the mother of all. I opened my mind to Imbas, and in the light, I finally saw her. The H A G.

2.

The greatest wisdom is seeing through appearances.

Atisa, Buddhist leader and master

I think I have become too good at this. It is why I have so few friends. I’m not interested in the outer trappings of friendship. I want the collision of two souls, and it is too much to demand. Skin is a barrier. It keeps us out of the other’s mind. Privacy is important, never more so than today. But if we don’t let anyone in, we become isolated, and loneliness can be destructive. Once we were like a hive-mind, all pulling together for the benefit of all. Now we are all individuals. Divided from each other. We look at each other’s skins and make judgements. We have forgotten how to see through our outer trappings. We have forgotten where the value of a person lies.

3.

One can wait for a whole lifetime for the reality we want and miss the one we have in our hands.

Thomas K. Carpenter, author

I have been sleepwalking for much of my life. Somehow, not quite being present. Enjoying life, but in the way a surfer skims the wave, never falling into the deep. So much life has passed me by without my notice. But it’s never too late. I am reaching out. I am profoundly grateful.

4.

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

Marcel Proust, French novelist, literary critic

What we seek is always hiding in plain sight, I have found. Stowed in stone, whittled in wood. Waiting to be discovered. The only way to search is to question everything, what you are told, even what you already believe. In college, they called it ‘critical thinking’. We don’t need new eyes, just a new way of seeing that involves all of our senses.

5.

The fact that logic cannot satisfy us awakens an almost insatiable hunger for the irrational.

A. N. Wilson, English writer and journalist

Irrational = not logical. But who gets to decide what is and is not logical? Science, it seems, has not provided all the answers, but attempts to divert us from seeking elsewhere. Science has made us one-dimensional, where embodiment feels like imprisonment. In the old stories of Ireland, learning is undertaken through the five senses of our embodiment: sight, sound, smell, touch and taste. They allow us to be part of our environment, to be sustained by it and to offer it sustenance in return. But the physical is only one aspect of existence. We have life and mind and soul, too, which reside within the physical, and we are not alone in that, but we find it so difficult to see. It is irrational-illogical to yearn for something we already have.

Freeing the H A G in the Stone

I understand that the squatting position of the Sheela-na-gig and the prominently displayed vagina being held open could lead to interpretations of child-birth. But I want to dig a little deeper than that.

According to Jack Roberts, Sheela, or Sile means femininity, but also refers to the word ‘sídhe’. This implies an otherworldly female. He also suggests that that the ‘gig’ part of the word, Sheela-na-gig, could derive from ‘guí’ or ‘guígh’, the Irish word for pray. This otherworldly female may therefore be a goddess whom one might pray to, perhaps for fertility?

However, in some cases, these stone figures have been Christianised with the names of saints; the figure above a doorway in a church in Ballyvourney, for example, was named after the local female saint, St Gobnait, and Roberts describes how “pilgrims to this shrine still rub the vulva of this sheela, a common practice that is thought to have a magical fertility or healing power”. 3

But what really interests me is this: Roberts claims that Sheela-na-gigs “were commonly referred to as ‘the hag’ or ‘cailleach’.” 4 When I first read this, it really struck a chord, because it confirmed my own suspicions.

As part of my Bachelor’s degree, I took four modules which comprised the study of Irish Cultural Heritage. I learned that there was no evidence underpinning the popular theory of the Sheela-na-gig as a pre-Christian fertility goddess, that they were nearly always associated with churches in Ireland and Europe, and were probably therefore introduced by the Anglo-Normans, who were great church builders.

I didn’t question it at the time, but it lodged in my mind, and surfaced later, during my time at the museum. As Carl Sagan said, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”; therefore, in the absence of stone Sheelas from the earlier pre-Christian period, is it possible that there is other evidence which has been overlooked, perhaps misunderstood figures made from materials which were easier to work with primitive tools, materials that were organic and perhaps less likely to survive the passage of centuries, as stone did. Wood, perhaps?

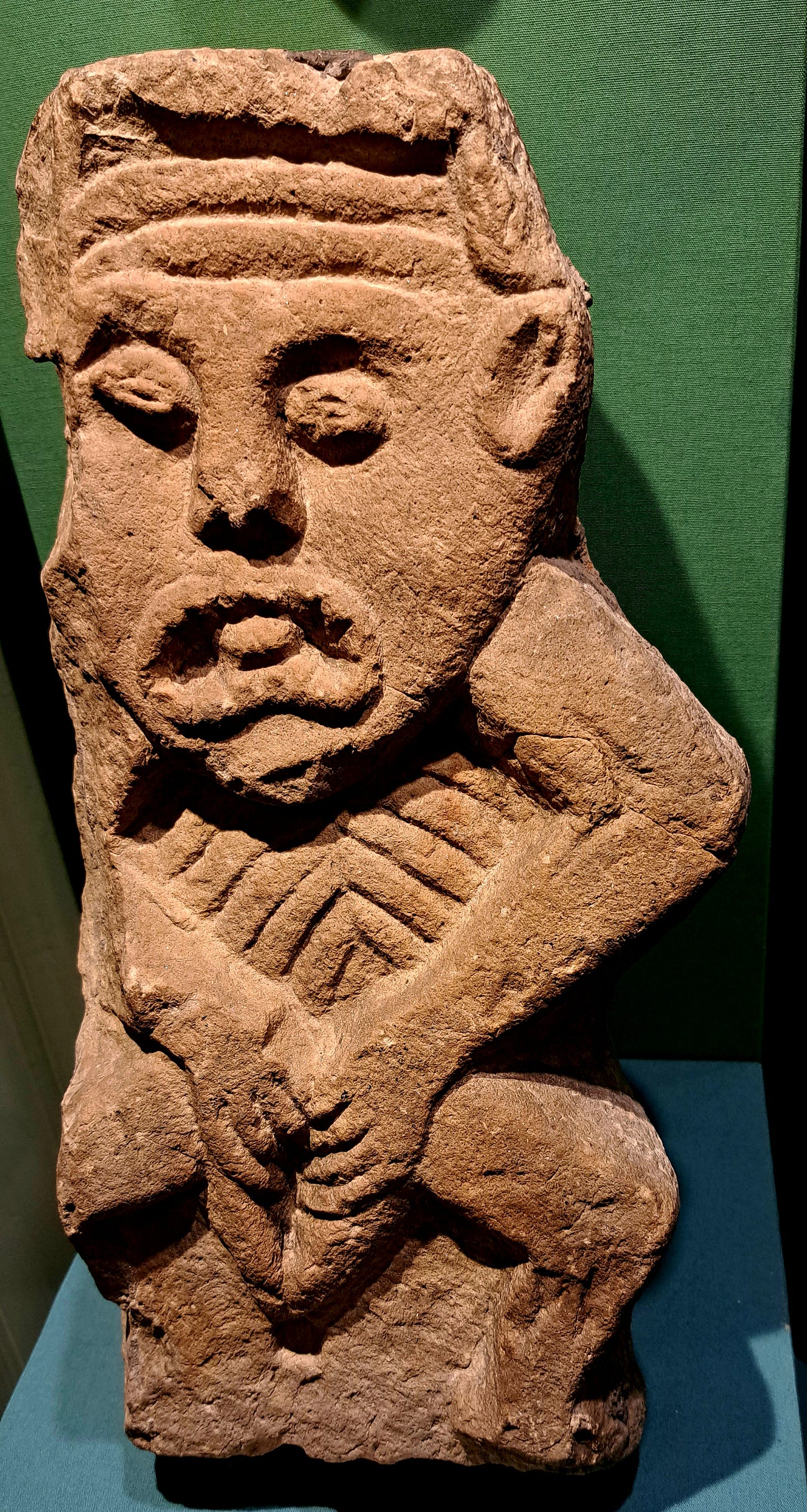

I want to show you now my favourite exhibit in the Cavan County Museum:

The late bronze-age Ralaghan figure is carved from the trunk of a yew tree. Standing just over a metre tall, it dates to between 1096–906 BC. Currently housed within the Kingship and Sacrifice exhibition at the National Museum of Archaeology in Dublin, the replica pictured above can be seen at the Cavan County Museum and is an excellent likeness of the original artefact. Discovered lying on its face in a bog near Shercock in County Cavan during the early twentieth century, the Ralaghan idol, as it was known then, was presumed by antiquarians to be male, the well defined hole in the pubic area interpreted as the site for the lodgement of a stone phallus, although no such object was ever found with or near the figure.

Now compare the Ralaghan figure with this one:

The Balachulish figure dates to around 600BC and is currently housed in the National Museum of Scotland. It was found in a peat moss bog in 1880, again lying face down and covered with a wickerwork woven vessel or shield. Unlike the Ralaghan figure, it was identified as female from the start.

The figure then stood approximately 1.4m high, and was believed to have been carved from oak, but has since been identified as alder. Like the Ralaghan figure, she has barely a suggestion of arms, no breasts, but a well-developed pubic area. She has two pieces of quartz lodged in her eye sockets. In all respects, much like the Ralaghan figure and the stone Sheelas, she appears fairly androgynous but for the prominent vulva. Unfortunately, she was not well-preserved and allowed to dry out, which caused much damage, but this early sketch of her when she was discovered (see above) gives a fairly good idea of her original appearance. 5

The National Museum of Scotland describes “[t]he slender body” as “naked, and seems to be hairless. The lower part is definitely female, but the chest is flat, so the figure may represent a girl or young goddess”; 6 They see her as a fertility figure, or a local goddess to whom travellers would make offerings for safe passage across the dangerous straits between Loch Leven and the sea.

In other words, they are presenting a hairless, breastless pre-pubescent female child as a fertility goddess. Does it not seem more likely that she was in fact a representation of the hag, the Cailleach who was connected with the landscape, the weather, and the sea? Would she not have had far more power in such a potentially hostile and dangerous environment for travellers?

Jack Roberts claims that “[e]arlier predecessors of the sheelas were carved in wood and the few surviving wooden idols share the same archaic art form [as the stone sheelas]. 7 He does not elaborate on the subject, or offer us examples. However, I think it is clear which ‘idols’ he is referring to.

I believe it is quite possible that these wooden figures may have been early versions of what we now know of as Sheela-na-gigs; that they were connected, not with traditional notions of the fertility goddess as we think of her today, but with the Cailleach as ultimate deity of female power.

As such, it is not surprising that she was appropriated and subsumed by Christian practices, her identity and power gradually diminished, erased, and finally forgotten.

Have you learned something new in today’s post? I certainly did in writing it, although this connection between Cailleach and Sheela-na-gig has been percolating for some time. Maybe you know someone who would also enjoy this post?

Hagstone kindly gifted to me by artist Jane Brideson, which she has decorated with symbols from the back wall of the inner chamber of Cairn T, Loughcrew © Ali Isaac

Jane Brideson is an artist and a follower of the Cailleach. I had the honour of meeting her when she exhibited her incredible artworks on the Cailleach a few years ago at Loughcrew. I did not know then that I too would be one day called by the Cailleach! Her paintings are beautifully detailed, intuitive, and poignant. She has designed a highly desirable set of Oracle cards, The Wisdom of the Cailleach; you can check them out on her social media and sign up to her waiting list if you would like your own set. You can connect with Jane on Instagram and on Facebook

Secrets stowed in stone, whittled in wood: Freeing the H A G in our bone and blood

September is already upon us, and through this year with the Cailleach so far I have come to understand her in so many of her guises: the woman in the grey veil, the wise-woman, the sovereignty goddess, the queen of Lughnasa, some of them unexpected to me, but none so much as my gradual awakening to her presence as Sheela-na-gig. She really is proving herself to be, as Roberts points out, the “ultimate female deity as symbolised in the Cailleach or HAG, the goddess or the image of female spiritual power”.

That she is not one, nor three, but showing her presence in multiple facets of female being is not a surprise to me, though; as an ordinary mortal woman I feel my identity shattered into many fragments, some of them pulling in opposite directions as I try to acknowledge and honour them all: mother, wife, employee, activist, writer, healer, feminist, sister, friend, student. It has been a struggle, at times, when all I want to be, is me. But after all these decades in which I have put myself to one side as I concentrated on one role or another, I’m not so sure anymore who ‘me’ is.

By revealing herself in all her forms, the Cailleach is helping me to understand that all these scattered shards of me are part of who I am, but that I need not carry the weight of myself around in pieces like a wounded or broken thing. There are some parts of me that I have not mentioned here, that have held me back, that I now need to lay to rest so that I can heal more completely and move on into my power. They are part of my private journey that I am not willing to share here, at least not yet. Understanding this is a relief, although I don’t expect the slicing away will be easy. Letting go never is.

The Cailleach as Sheela can teach us many things. Secondly, for me, the withering of the female form as I age, the breasts which lie shapeless and dormant that once nurtured new life, the hair which is greying and thinning, the thickening waist, the creaking knee joints, these are all inevitable signs of the aging process that I see carved into her likeness, that patriarchal norms use to turn us against ourselves, to strip away our divine feminine and thus our value. The Cailleach as Sheela is defiant; she is very proudly displaying her divine feminine. That power cannot be taken away, not by age, and certainly not by the patriarchy, unless we choose to view ourselves through the male gaze. The Cailleach as Sheela is urging us to step forward into our power.

We are Multiple and One. And we must step confidently forward into the Power of the Divine Female, feed that small flickering flame inside us until it roars. The lesson is right there, if we open our eyes and look, stored in stone and whittled in wood, the simmering fire in our bones and blood.

Roberts, Jack. ‘The Sheela-na-gigs of Ireland - An Illustrated Map and Guide’, Bandia Publishing, Galway, 2009.

Roberts, Jack. See footnote 1.

Ibid.

Roberts, Jack. See footnote 1.

As usual, very thorough, thought provoking, and stretching out the possible interpretations and adding new ones. Lovely job Ali. Two main areas I have been taught in the sheela realms.

The first was a family one, and very water related. At family gatherings, that went into quite deep conversations. With ‘sheela’ chat, they would talk of water actually being the womb within where the building blocks living temples all shapes and sizes would be made and assembled, then let out to the world to do their things. Then when the living body was done, all that water then leaves the body to rejoin all other water again in some way.

So the family teaching was more about the sheela na gig being the way of the landscape. Where there is water, there is life. Where there is just ‘dust’ no life as it needs water to do the construction. They believed in a lot of human burial places being close to water was for that purpose.

Second ‘teaching’ for me was doing stone mason contracts on Iona. The supervisor, ‘Attie MacKechnie’ had a huge passion for stone mason’s heritage. To him, stone masons had their own culture. As far as he believed, all ‘sheela na gigs’ were carved by men. But I am sure we have no proof of this. To him this was a mason’s symbol of ‘you are entering into a sacred place’ and that hairless etc. was to bring full attention to the vulva. Not as a sexual communication but again related to water.

Attie believed the Medieval masons lived in constant tension with the Abbots and monastic sites people due to their constant disregard of gaelic heritage and values, of which water and heritage trees were a large part off.

So Attie believed that the old masons made up a yarn about carving sheea na gigs as ‘gargoyles’ convincing the abbots that they were for keeping away evil spirits. But the real purpose was giving the local people a shock message such as “as you enter this building you will be told about gospels, psalms, the devil, and sin … but never loose your sacred heritage of connection to the sidhe, water, and earth goddesses. Enter this place sustaining your sanctity of the watery womb and creation, while these men may attempt to purify you with their gospels.”

So though the sheelas were ‘sold’ to abbots as being a tool for keeping ‘evil sprits’ out, they may have been tools to stop ‘patriarchal’ conversions taking over the people entering these church temples?

Attie’s story is surreal, but break it down to basics, and to me it makes a lot of senses. And literally, about allow our senses to rule over language.

A fascinating read and I so agree with you that they cannot possibly be fertility/birth figures. So much discussion as to how old they are and what they were used for. In Cork there are four that seems to be slightly connected to holy wells but I think they've all been brought from somewhere else. I too think they represent the hag, and I think they have been placed (often on castles or churches) to scare the bejeesus out of the evil eye and to offer protection. All so interesting and they still invoke fear, revulsion, admiration.