“Now this is what used to kindle the warriors who were wounded there so that they were more fiery the next day: Dían Cécht, his two sons Octriuil and Míach, and his daughter Airmed were chanting spells over the well named Sláine. They would cast their mortally-wounded men into it as they were struck down; and they were alive when they came out. Their mortally-wounded were healed through the power of the incantation made by the four physicians who were around the well…. another name for that well is Loch Luibe, because Dían Cécht put into it every herb that grew in Ireland.”

Healing in Mythology

In ancient times, Ireland was renowned for the skill of its physicians, particularly their herbal-lore. Mythology tells us not just of famous battles, brave warriors and tragic love stories, but tales of miraculous healing, too.

Of all the Irish Gods, the most well-known and beloved of them all were those who practised healing, such as Brigid, Lugh, Dian-Cecht and his son Miach, and daughter Airmid, who was greatly skilled in herbal lore.

Dian-Cecht came to Ireland with the Tuatha de Danann invasion over 4000 years ago as King Nuada’s physician. When Nuada’s arm was struck off in battle, Dian-Cecht replaced it with a fully working one of silver. Later, his son, Miach, was able to cover the silver arm with skin, and thus restored and unblemished, Nuada was able to return to his position as High King of the Denann people.

The first bionic arm, perhaps, or at least a fully functioning prosthetic one.

When the Red Branch Knights of Ulster rode into battle with Cúchulainn, they were accompanied by a medical corps. Each one of them carried at their waist a bag known as a lés (pronounced lace), which was full of medicines, ointments and medical implements.

Historically, as with most aspects of early Irish society, the role of the physician was governed by the Brehon Law. If someone was injured by another, the victim was entitled to be paid compensation by his aggressor. Likewise, if a doctor failed to heal his patient, he was required to pay a similar compensation, and return any fee paid by the patient.

The early Irish even had hospitals in which to treat their sick and wounded. The Tain refers to a hospital at Emain Macha (Navan Fort, near Amagh) known as Bróinbheg (pronounced brone-ver-rig), which means ‘House of Sorrows’… which to be honest, doesn’t sound too promising!

The Brehon Law had very strict rules pertaining to hospitals; they were required to be kept clean and well-ventilated, had to have four open doors, and a stream running through the centre of the floorspace. Patients were expected to pay for their food, medicines and physician’s services, so it is quite likely that only the wealthy ever visited a hospital for their healing.

As with Nuada and Dian-Cecht, kings and nobles employed their own personal physicians, although his services weren’t always exclusive to his employer. He was provided with land and a home at the expense of his employer, and was also paid for his services.

The role of a physician was a hereditary one. He passed down his skills and knowledge to his offspring, and often to apprentices living with the family. In later years, this wealth of information was written down in manuscripts and books. The most famous of these is the Book of the O’Lees.

Of course, medical services were not just required as a result of injury from battle. Disease spread like wildfire through communities which were rapidly growing, following on from the Neolithic farming revolution.

Plague was common. Plague victims would be buried in specially marked graveyards, which Cormac’s Glossary calls tamhlacht, meaning ‘plague grave’. Tallaght near Dublin is named after a tamhlacht; it is said that here nine thousand Parthalonians were buried after they all died from plague within a week. The Partholonians were the second wave of invaders said to have arrived in Ireland three hundred or so years after the Great Flood when the island was still uninhabited.

It was believed that disease could not travel over the sea further than nine waves distance, a thought which persisted into Christian times. This is why during times of epidemic people fled to safety on small coastal islands, or established colonies and hospitals there for the afflicted.

The early Irish developed some amazing skills and techniques which would be impressive even by today’s standards. They were able to:

1. Stitch wounds.

King Conchobar mac Nessa had a wound stitched in his head with thread of gold to match his golden hair.

2. Use suction to remove infection.

Female physician, Bebinn, drew out poison from the leg of Caoilte of the Fianna, using two tubes called fedan. This technique was called ‘cupping’. She also prepared five medicines for him by steeping herbs in water, then administering them to him individually over a period of time, until his full health was restored.

3. Make sleeping potions.

Warrior-woman and teacher, Scathach, gave a sleeping potion to Cuchullain to prevent him from going into battle. It was said to be so strong, that a normal man would have slept for twenty four hours. Cuchulainn, of course, awoke only after one.

Grainne administered a sleeping draught to all the guests at her wedding to Fionn mac Cumhall by slipping it into the wine supply, so that everyone but her lover, Diarmuid, fell asleep.

Although these examples are not medical ones, they do imply that making such medicines was not unheard of.

4. Build saunas.

Early Irish sweat-houses look like little stone beehives with a low doorway, and can still be seen dotted around the landscape today, although their true purpose is one of debate. They were called Tigh nAlluis (pronounced Tee-noll-ish). A fire would be lit inside, in which stones were heated. The ashes would be scraped out, and water sprinkled onto the stones to produce a heavy vapour.

The patient would crawl inside, and the door sealed. Afterwards, he would be plunged into a trough of cold water and then emerge to be rubbed till warm and dry again. This treatment would be repeated until the patient was pronounced cured.

5. Perform surgery.

We have already learned that Dian-Cecht fashioned a fully working arm of silver for his King, Nuada. Inevitably, attachment would have required some form of surgery. (Hopefully, his sleeping draught was more effective than Cuchulainn's).

In AD 637, following a head injury received at the Battle of Moyrath, a young chieftain named Cenn Faeladh mac Aillila was taken to receive treatment from St Briccin, a renowned scholar and surgeon, at the monastic chool of Tuaimm Dreccon (Tomregan) in Breffni (Co Cavan, where I live; Tomregan is near Ballyconnel, I feel a field-trip coming on).

“the virtue is not that the brain of forgetfulness was taken out of the head of Cenn Fáelad, but in all the book-learning that he left after him in Ireland.”

- the Cycle of the Kings

Not only did Cenn Faeladh make an excellent recovery, but his memory improved to such an extent that he became word-perfect. He stayed on to study Brehon Law, Poetry, and History, and produced three great scholarly works on Law, Grammar and History.

It is thought that he was healed by trepanning, a surgical intervention which involves drilling a hole into the skull, usually to release pressure. Evidence of this has been found on skulls dating back to Neolithic times.

Google Celtic healing, however, and you’ll encounter something quite different altogether. Also known as Bio Energy Therapy, it is reminiscent of a far eastern treatment called Reiki.

Reiki is based on releasing blocked energy in the body through zones known as ‘chakra’. It is a gentle yet powerful non-invasive treatment still practised today which is said to be able to cure a whole range of ills and promote relaxation and a sense of well-being.

I have personally had powerful experiences of Reiki. One of the hand positions (cupped over the eyes, and said to enhance the third eye) is very similar to how Cormaic described the beginning of the ritual of Imbas Forosnai.

In Ireland, the chakras were known as ‘doors’ through which energy in the form of light was brought into the body to enable healing via Imbas Forosnai. Whereas the energy in Reiki is channelled from the universal life force through the head, in Celtic healing it is drawn from the earth.

This mystical, spiritual aspect of healing can also be found in mythology. Fionn mac Cumhall was said to have acquired it by eating the Salmon of Knowledge. After Diarmuid eloped with Grainne, a reconciliation was organised which involved a boar hunt. Diarmuid was mortally wounded by the boar, but could have been saved by receiving a drink of water from Fionn’s healing hands. Unable to forgive Diarmuid for his misdemeanour, twice Fionn let the water drain through his fingers. Finally he relented, but by the time he returned with water cupped in his hands, Diarmuid was dead.

Ireland also has many holy wells named after various saints, but most often attributed to Brigid or Patrick. Often associated with healing, each well is typically devoted to a particular ailment, such as eye complaints, or warts, and such like. The afflicted must circle the well deiseal-wise, while reciting certain prayers at prayer stations situated along the route.

Although adopted by Christianity, these holy wells were undoubtedly pagan in origin, and known as Wells of Healing.

The Cath Magh Tuireadh gives a fine example of this; at the Battle of Moytura, Dian-Cecht established a well of healing at a small nearby lake with his children, Miach and Airmid. Into it, they threw many herbs and walked its perimeter muttering incantations.

The wounded and exhausted warriors bathed in it every night, emerging refreshed and fully restored. It was said the healing magic was so powerful, that even the dead could be brought back to life.

This gave the Danann a distinct advantage when battle was rejoined every morning, which did not go unnoticed by the enemy. The Fomorians sent a spy into the Danann camp to suss out their secret. When they discovered the Well of Healing, they sent a company of men to secretly attack the Danann camp while the Danann warriors were occupied in the battle.

The Fomorians filled the Well with boulders dragged from the River Drowse, so that it was impossible for anyone to enter the water and bathe in it thereafter. The Well of Healing at Moytura is said to be located beneath a large cairn at Heapstown. However, this cairn has never been excavated so the location of the well remains a mystery.

Wisdoms

1.

“Silence is a place of great power and healing”

Rachel Naomi Remen, author, paediatrician, teacher of alternative medicine

What is silence? There is only quiet, and absence of sound. They are not the same thing. If I am in a quiet place but I can hear a voice talking, even if it is contained within my head, is it still quiet? Am I experiencing silence?

When I think of quiet, I think of Lough Oughter. Even the water did not murmur, the trees did not waver, the wind did not stir, but the air was alive with the thrashing flight of large water birds, with the mating calls of whooper swans and mute swans and the beating of huge wings upon the surface of the lake. I could imagine that humankind had fallen from existence, but for the ruined face of a tower that jutted, cannon-ravaged, from the water; human history screamed at me across the water, the sound of anguish and loss and terror.

I sat on a rock with my toes in the water, and fell into it all. It was wildness, a welcome drowning. I fell out of the contemporary world into something primeval. Amid the commotion, I experienced complete silence. I achieved stillness. And joy.

Yes, it was powerful, so much so that the memory still rocks me and draws me back. And without a doubt it was healing. I was rejuvenated. But there is no peace in landscape, not truly. We must love the flawed silences honestly.

2.

“The wound is the place where the light enters you”

Rumi, poet, scholar, mystic

This was hard to grasp. Why? What hurts us, heals us. Simple. We are changed, we grow. The body forms a scab over a wound, beneath which new flesh is laid, pink and tender as a rosebud. The body is repaired and it does this work without input from you. It knows what to do to heal itself. We exist in the same space as this animal body; why do we ignore and mistreat it? Instead, we could learn, let the light of Imbas flow into our centre, remove the pain and heal ourselves. Light must have an entry point. Make a hole and let it in.

3.

“the art of healing comes from nature, not the physician. Therefore the physician must start from nature with an open mind”

Paracelsus, physician, alchemist, philosopher

I walk. I thrust my feet, one in front of the other, in a line which takes me out of my home and into the wild landscape. There, I discover plants that cannot be seen through the window of a speeding car. I am drawn to their colour first, their scent, the improbability of beauty which can go so unnoticed. Disregarded as weeds. Stars hiding in broad daylight. The wonder of modern technology helps me with identification, and what I discover brings tingling light into a part of me I did not know existed. Once, these plants were foods, they were medicines, they were poisons. They had charm and purpose and mystery. Why did MANkind think they could improve on something which was already there and freely abundant?

It seems to me that science closed minds rather than opened them. Medicine could only be powerful if it was commodified. In the control of the wise-woman healers of old, money was not exchanged for medicine. In the 21st century, in most of the ‘developed’ world, medical care is based on profit, and those who can’t pay must suffer. In Ireland, doctors make a good living out of private consultancies, health insurers make a more than healthy profit out of people’s sickness. If you can’t pay for either, you are welcome to join a very long queue. This is what we call civilisation.

4.

“It is reasonable to expect the doctor to recognise that science may not have all the answers to problems of health and healing”

Norman Cousins, journalist, author, professor, world peace advocate

I learn through my children that doctors are not Gods. When a doctor says to you, “there’s nothing more I can do” while your child writhes screaming in your arms as they have done for days and days and nights, you learn this. You learn this when a doctor says to you about your child, “I’m sorry, we have done everything we can, now it’s down to him”. Doctors are men of science, but they are also fatalistic. Yet still, without the learning and knowledge of doctors, two of my three children would be dead. Had they been born fifty years earlier, even science could not have saved them. I am a fortunate mother, oh my gratitude knows no bounds! But sometimes science has no answers, and the mother must step up. She will try anything… no, not anything… everything. All the things the doctors do not believe in, would discourage you from, because they are not science. The things which threaten their own inadequacy. The things which are too obvious to be true. The things which need digging out from obscure lairs. The things which are the opposite of what they tell us and thus defy their expertise. The things which they say are ‘hocus-pocus’. But sometimes ‘hocus-pocus works’, although we don’t yet understand why. I have two living children who are evidence of that.

5.

“the greatest healing would be to wake up from what we are not”

Mooji, spiritual healer

I feel this. From our earliest times, we are told who and what we should be, usually along the lines, or should I say binaries, of gender and class and race. With a dash of ableism thrown in. Since the Covid pandemic, this has boiled down into a concentrate I can no longer absorb. It is too much for me. This world is too much for me. Does this mean I have awoken from what I am not? I am no longer asleep. To be awake is good, no? I mean, I love my sleep, but I don’t want to sleepwalk through life. To be awake is painful and raw. It is rebirth. It is the wound through which the light, the Imbas, enters. It is like the rising of the sun. It is a movement which is gathering pace.

Wise-Woman or Witch?

It seems, according to early Irish scribes, that there were common cures known to all, in much the same way that today we would give paracetamol for a headache, or stop a bleed with pressure, or apply a plaster to a cut. The warriors of the Red Branch carried paraphernalia which allowed them to treat battle wounds, for example. For some though, like Dian Cecht and his son, Miach, and his daughter, Airmid, healing was a profession and a gift, secret knowledge known only to a few, that was handed down through the generations from parent to child.

It also seems that there were areas of specialisation; Dian Cecht and Miach were able to create new limbs of silver and coat them in living skin, whilst Airmid was a skilled herbalist. Additionally, there was magic involved: the incantations at the Well of Healing which not only rejuvenated exhausted warriors but brought the dead back to life.

Brigid, as goddess and saint, was also said to be a healer, and her skills also involved a higher power: she restored sight to the blind, voices to the mute, and she restored the chastity of nuns by performing abortions, “causing the foetus to disappear without coming to birth and without pain”, according to Cogitosus.

Earthly skills and knowledge, such as herbalism or surgery, worked alongside the miraculous and magical. Furthermore, the art of healing was not gendered.

Just the other week, I was talking with colleagues at the museum about local people who ‘had the cure’; these were usually the seventh son of a seventh son, and when I asked if a seventh daughter might inherit the cure, I was told oh no, absolutely not! However, I have seen a list of people who ‘have the cure’ in my local area which is kept in a library, and many of these people were women.

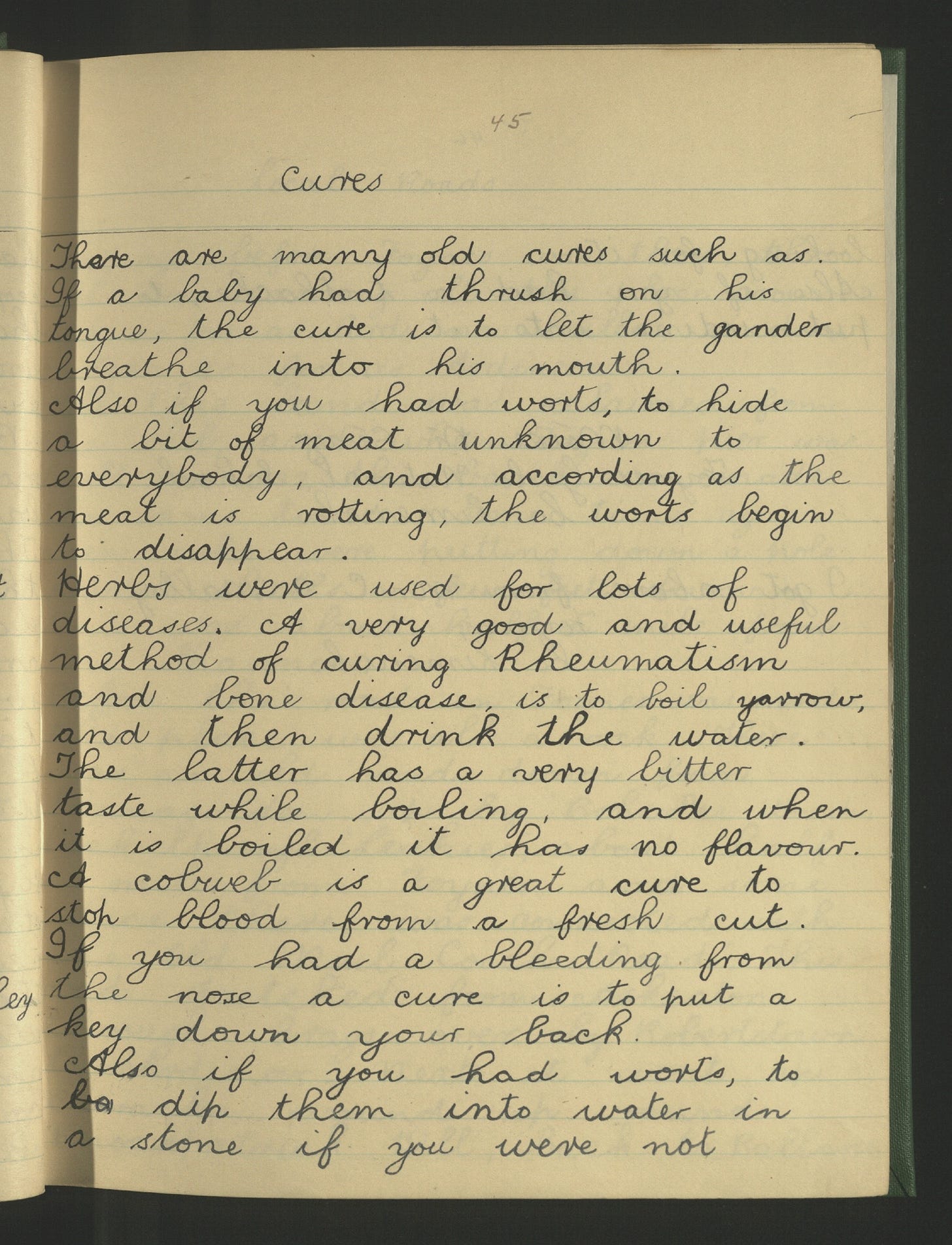

As you can see from the image above, folk remedies for common ailments from the early part of the last century could be quite outlandish: curing whooping cough in a baby by allowing a gander to breathe into the baby’s mouth, for example, or burying a piece of meat as a cure for warts, and as the meat rotted so too would the wart decay.

However, for something more serious, the services of the local healing woman were required.

Readings from The Book of the Cailleach: Stories of the Wise-Woman Healer by Geróid Ó Crualaoich #19. Incident recounted of a healing woman from Baile Bhoithín - I, and #24. Incident recounted of a healing woman from Baile Bhoithín - III.1

Ó Crualaoich makes no distinction between the healing woman and the wise woman from folklore; to him, they are connected equally to each other and to the Cailleach. Although the narrator of #19 consistently referred to Eibhlín as bean leighis (woman of healing) rather than bean feasa (wise woman), ÓCrualaoich suggests that “the application of the herbal substance with ritual formulas of behaviour and speech” is indicative “that more than vernacular herbal pharmaceutics is involved”. 2 The narrator is at pains to make clear that Eibhlín is no ordinary herbalist but possesses the diagnostic and divinatory powers of the wise-woman as well.

It is interesting, here, that even the priest has recourse, on occasion, to call upon her services, in spite of his denouncement of her from the pulpit. Clearly, whilst the church viewed her as a threat to their authority and by extension, to the morality and well-being of their flock, the community viewed her as a valuable service-provider and asset whose power came not from the devil, as the priest claimed, but from the "native ancestral Otherworld" of the Sidhe.3

Eibhlín herself does not see her work as a challenge to the authority of the priest or Christian faith; "I'm not interfering with him in any way", she says. Neither does she deny his horse healing despite the priest's public slander of her. Rather, she feels vindicated; her comment, "Now he has been shown that I have knowledge and healing" indicates that she has proved her skills to be genuine and effective, and not 'of the devil'.

It is important to note here that there is no indication of any payment or benefit-in-kind exchanged for Eibhlín’s services. Her cures are freely offered, along with her generous hospitality towards those who have travelled from afar to avail of her healing powers.

In the first story, the cure is not herbal but mystical and otherworldly, carried out across distance without the healer having seen the injury, but accompanied by Eibhlín’s foreknowledge of the incident. The cure she effects is reminiscent of Reiki healing, which can also be carried out by intent across distance. It is not explicitly stated by the narrator that the mare was cured, but the fact that the priest never again spoke a word against her is evidence enough that the cure worked.

In the second story, the cure is herbal, although it is accompanied by a warning not to look back before the bearer reaches Mám na Gaoithe, otherwise the plant will disappear. In this, we find Eibhlín is asserting her magical authority. His failure to follow her instruction is treated with empathy, and she gives him a second chance, but she also stresses he will not get a third; she is demanding his trust and obedience and will not accept less. When he complies, the herb survives and his sister is healed.

At the end of the narration, the sighting of Eibhlín’s fairy lover connects her with the Otherworld from where she draws her knowledge and power. As such, she is the conduit between the community and the fairy realm which “lies beyond the ‘normal’ ranges of human perception”, and which they are determined to keep alive, despite their Christian faith and the ministrations of their priest.

Sylvia Federici associates the European witch hunts of the earlier sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the rise of the modern capitalist world via the “dismantling of communitarian regimes and the demonization of members of the affected communities” such as ‘witches’. 4 The witch hunts in Ireland were not as widespread as they were elsewhere; our stories show however, that the demonisation of healing women continued in Ireland but was resisted by local communities, rather than embraced.

The witch, "a healer and practitioner of various forms of magic that made her popular in the community... signaled her as a danger to the local and national power structure in its warfare against every form of popular power", Federici claims, and goes on to write, "[i]n the witch, the authorities simultaneously punished attacks on private property, social insubordination, the propagation of magical beliefs, which presumed the presence of powers they could not control"; we can see evidence of this in the priest's denunciation of Eibhlín in our stories. The stories also indicate that he was not successful.

But what does this have to do with the Cailleach? In Ó Crualaoich’s book, the healing woman is most often portrayed as being a lone older woman who has knowledge of the local landscape and all that grows in it or moves upon it. She is the physical manifestation of the Cailleach on earth, or her representative and associate, at least. She also functions as a conduit between the mortal and otherworld realms, interceding on the community’s behalf in times of need and in their best interests. That she consorted with a fairy lover further compounded her existence as a human woman who existed in the liminal space between the two dimensions and was accepted in both.

In Federici’s book, such women were impoverished and denigrated by the new and emerging world order of capitalism and science; in fact, they were tortured and killed for their ‘loose morals’, consorting with ‘the devil’, their medical ministrations diminished or described as ‘dark arts’. Their punishment was a lesson to all women who might think to stray from the subservient role desired by state and church. The Cailleach was the antithesis to this new female role model, and as such, she had no place in the written record. She lived on in vernacular culture, however. That an old woman without status, single and independent, without land or money could survive by wielding the power of the magical over a community was not something the authorities were prepared to permit.

Lessons from the Healing-Woman

My first lesson comes from Airmid’s story. Her role involved the painstaking invisible work of understanding and categorising herbs and plants. Her father and brother did the more exciting glamorous work of healing kings, devising metal prosthetics, and surgery. The new skills of the young and upcoming Miach caused bitter resentment and jealousy in his father, to the extent that he was prepared to murder his own son. Among the male physicians of mythology, then, there was competition, kudos and ego. In her grief, Airmid devoted herself to the study of the plants growing from her brother’s grave, but in her quiet work, even she did not escape her father’s wrath, and he destroyed all her work.

This suggests to me that herbalism was seen more as women’s work, rather than worthy of the great male physician. In my H A G years, I have become increasingly drawn to the wild plants which flourish in the landscape independent of humankind, rather than those which are grown in the garden. This is what I want to study, like Airmid: the power of plants on and in the body. I see plants as food, nutrition as medicine. I am not so much interested in correcting ailments, as avoiding them completely, and I wonder to what extent wild plants can help us do this. Like Airmid, this requires patience, determination, and lack of ego.

I will therefore be watching Lucy Ní hAodhagáin’s new project with interest!

My second lesson comes from the human healing-woman. I shudder to think of the suffering of all those women (and some men, it has to be said) who suffered so cruelly during the witch-hunts. Scotland has begun its own healing process with a formal apology from the Scottish government for the the murder of women accused of witchcraft, and another from the Church of Scotland; a campaign for a national monument of commemoration is now under way. We have work to do if we wish to prevent the misogynistic persecution of women in all its forms. In Ireland, the campaign to recognise Brigid as matron saint has been part of that process. The campaign for justice for mother and baby home survivors is another. And there is more to do. I will step up to play my part, as we all must.

Cath Maige Tuired: The Second Battle of Moytura, Author unknown, trans. Elizabeth A. Gray, CELT UCC.

Ó Crualaoich, Geróid. The Book of the Cailleach: Stories of the Wise-Woman Healer, Cork University Press, 2022.

Ibid, p. 179.

Ibid, p. 180.

Thank you so much John! I really value your insights. I have started with fermenting foods but not ventured into brewing or distilling, but yes, I would have thought that was vital for the work of making medecines from plants. I'm not sure yet how far I will go in this project, at the moment just going where it leads. Your knowledge is vast! My brain does not store that much! 🤣🤣🤣

From “I feel this…” to ”a movement which is gathering pace.“

This whole section is so thought provoking. I read this part 3 times and it really resonated with me.