The Evolution of the Cailleach

From earth goddess to wise-woman to witch to... unpaid babysitter and miserable cat-lady?

You may have seen posts on your social media feeds recently that claim studies have shown that humankind have evolved their women to survive beyond menopause solely for the purpose of helping to rear future generations, and that we are one of the few species on the planet that have developed in this way.

Well. Fuck that, if you don’t mind me saying.

My children have not made me a grandparent yet, and I have a feeling it will be some time before they do. If and when grandchildren do come along, though, I know I will love them with all my heart, but I don’t see the purpose of my remaining time on this planet as a duty to help rear them.

My child-rearing days are done and over. I feel no shame or guilt in declaring that I now have other priorities, that, for the first time in my life, centre not on societal expectations about what a woman should do and be, but on how I want to live and how I see myself.

Women who say such things are considered selfish. Ungrateful. Greedy. Spiteful. I truly don’t care. But I thought, in honour of International Women’s Day, which has just passed, and the upcoming Sheela’s Day, the quieter shadow of a festival following so close on the heels of her husband’s, St. Patrick’s Day, I’d drill a little deeper into this tedious ‘what is a woman’ debate, which is still ongoing since at least the 1960s, if not forever.

Céad míle fáilte, a hundred thousand welcomes to H A G! I’m Ali Isaac, and this email comes to you from the intersection of female senescence and Irish landscape, both mythical and natural. My book, Imperfect Bodies, will be published by Héloïse Press in the spring of 2026.

How much has changed. How little.

In her book, A Ghost in the Throat, Doirrean Ní Ghríofa writes: “ This is a female text, written in the twenty first century. How late it is. How much has changed. How little.”

She’s so right, and this whole idea of older women having evolved to rear grandchildren is all part of the patriarchal narrative that controls women: the maiden as desirable object, the mother as reproducer, the hag as grandmother.

A woman is more than a sex object, a walking uterus, a free home-help. She is a human being with wants and needs and rights.

Have I somehow missed the discussion about the purpose of a man once he reaches middle/ old age? Oh, you missed it too? That’s because there isn’t now, nor has there ever been, a public debate about who or what he is, or what he has survived to do in his dotage that justifies his continued existence.

Because enough of us do choose to become mothers, and then grandmothers who involve themselves in the lives of their grandchildren, the ‘purpose’ of our old age has has not arisen as an issue. Recently, though, it has emerged into the public arena as ‘fact’. As well as describing older women as miserable “childless cat-ladies”, JD Vance, US vice-president, has openly confirmed his belief that ““the whole purpose of the postmenopausal female” is to help raise grandchildren”. 1

It seems we regressing as a society here, heading right back into the dark ages where we are caught between the worst primitivities of the past, and the corruption and greed of modernity.

The Mysterious Transformation

How to control a woman who has moved beyond her breeding years? Well, in the distant past, she just continued; perhaps she farmed the land after her husband passed, or served her community as a mid-wife, or a medicine-woman, or a wise-woman who perhaps mediated with the dead or Sidhe on behalf of her community, or kept the lore of the land they inhabited, the lore of their ancestors, became a storyteller, or bathed the bodies and keened the passing of the dead. Whatever role she chose, it involved knowledge and power that was not common to all. This positioned her on the periphery of her community, where she was tolerated, accepted, perhaps loved or feared. Regardless, her services and knowledge were vital to the community, and through her long life, her acquired knowledge was unmatched. But then something happened.

According to scholar, professor emerita, author and activist, Sylvia Federici, the development of capitalism and the seizure, enclosure and commercialisation of common lands during the late medieval period changed the nature of rural life in Europe.2 This enriched the well-off and the better-off while impoverishing the poor even further, and older women were particularly affected. Existing customary rights that previously supported paupers were removed, begging prohibited, the giving of charity banned, all while prices were rising as a result of the riches and plunder of the New World flowing into European coffers.

Older women who were not in a position to support themselves or ostracised from family were forced to beg and were considered a nuisance to society. Some reacted with aggression, such as curses and threats against those who refused to help them. As society became increasingly mysogynistic, helped along by the Christian faith, the troublesome behaviour and ‘magical’ services of these women were seen as the work of the devil, and their punishment as witches served as a warning to all women who dared step outside the norms expected of them.

Interestingly, Federici describes how, by the seventeenth century, this process that had so revolutionised society, also transformed human relationships with animals and the natural world. Plant lore and healing was seen as devilish knowledge, and companion animals thought of as ‘familiars’. The keeping of animals, now reduced to ‘livestock’, and the growing of plants were transferred into the hands of men, where it became ‘husbandry’, while healing became the domain of doctors, who were also men.

In Ireland, however, things panned out slightly differently. The Cailleach persisted in all her forms within her local community well into the nineteenth century, as evidenced by the studies of Geróid Ó Crualaoich in his wonderful The Book of the Cailleach. Irish people, it seems, were loath to lose the services of their local wise-woman, despite the regular exhortations of their priests.

I share some of Ó Crualaoich’s work on the Cailleach in this post, as well as the role of healing in Irish mythology:

March: Wise-Woman or Witch?

Ó Crualaoich makes no distinction between the healing woman and the wise woman from folklore; to him, they are connected equally to each other and to the Cailleach.

The H A G in Irish Myth

In the Cailleach Project, I bring you the H A G in all her forms. I have brought Her to you as the Shaper of land, as the pregnant mother, as the personification of Winter, as the duality with Brigid, as Queen of the harvest, as the wise-woman and healer, as the Witch, as the Veiled Woman, as the Weaver, as the Sovereignty Goddess, and as the Sheelanagig. But I have never brought her to you as depicted so vividly in Irish myth.

I think this is so relevant to the topic of this newsletter and to where we are now, because then, as now, in terms of the female, youth is described as pure, aged as evil, beauty as good, aged as ugly. The hag is twisted and tricksy and full of malice. When she is not evil, however, she transforms into a youthful, beautiful, pure version of herself. Here are just a few exapmples out of many, but you will quickly get the gist.

Above all, note that in each story, the Hag possessed the power to kill men, or compete with them at their own game (usually brutal), or she has arcane knowledge or second sight, thus foretelling the death of men, or she has the power to confer the kingship upon numerous generations of men. She was extremely POWERFUL. No wonder she came to be feared and reviled. The storytellers made her ugly, and comical at times. They gave her a sweet, smooth face and said that was her real incarnation, implied the act of sex (rape? she only asked for a kiss, after all) tamed her. Old woman she might be, but mild-mannered little old grandmother she certainly ain’t!

So. Are you sitting comfortably? Let us begin…

Fionn Mac Cumhaill and the Hag in Black, Brown, and Grey

In this tale, a friend of Fionn’s discovers a house full of dead bodies. He hides among them, hoping to find out what had happened to them. After a while, a hag enters the cottage. After she has eaten she falls asleep, whereupon the hero bravely comes out of hiding and lops off her head as she sleeps.

[Gassan] saw an old hag coming into the house, having one leg and one arm and one upper tooth that was long enough to serve her in place of a crutch. And when she came inside the door she took up the first dead body she met with, and threw it aside, for it was lean. And as she went on, she took two bites out of every fat body she met with, and threw away every lean one.3

Fionn Mac Cumhaill and the Three Hags in the Cave of Ceishcoran

These hags carried spindles and were weavers, much like the three Norns in Norse mythology, I think. They also fought the Fenian warriors with swords, and wrestled them, which was certainly no mean feat. In the end, two were beheaded but the third escaped with her life by convincing the men she would help them with their tasks.

Finn and Conan came towards them, and saw the three ugly old hags at their work, their coarse hair tossed, their eyes red and bleary, their teeth sharp and crooked, their arms very long, their nails like the tips of cows' horns. 4

Prince Donnchadh O’Briain and the Hag of the Battle of Lough Raska

On August 15th 1317, the forces of Donnchadh Ó Briain and Richard de Clare attacked the army of Muireactach Ó Briain, who were sheltering in the grounds of Corcomroe Abbey. It is said that on the morning of the battle, Donnchadh met Bronach the Sorrowful washing limbs and decapitated heads in Lough Rask until the lake turned red with ‘blood, brains and floating hair’. She foretold that this would be the fate of Donnchadh and his men. They attempted to kill her, but she rose up screaming into the air and disappeared. Sure enough, they lost the battle, and by sunset that day, they were all dead. She was described thus:

She was thatched with elf locks, foxy grey and rough like heather, matted and like long sea-wrack, a bossy, wrinkled, ulcerated brow, the hairs of her eyebrows like fish hooks; bleared, watery eyes peered with malignant fire between red inflamed lids; she had a great blue nose, flattened and wide, livid lips, and a stubbly beard.5

Niall Noígíallach meets the Sovereignty Goddess

In the Echtra Mac nEchach (“the adventures of the sons of Eochaid”), Niall Noígíallach (of the nine hostages) was out hunting with his many brothers one day, when they stopped at a well to draw water. The well, however, was guarded by an ugly old hag who demanded payment of a kiss. Fergus and Ailill were disgusted, and refused. Fiachrae gives her a quick peck on the cheek, but she was not satisfied. Niall, however, exceeds her demand and sleeps with her. Afterwards, she transforms into a beautiful young woman and bestows upon him and twenty-six future generations of his descendants the right to the high kingship of Ireland. This is what she looked like when they first met:

Every joint and limb of her, from the top of her head to the earth, was as black as coal. Like the tail of a wild horse was the gray bristly mane that came through the upper part of her head-crown. The green branch of an oak in bearing would be severed by the sickle of green teeth that lay in her head and reached to her ears. Dark smoky eyes she had: a nose crooked and hollow. She had a middle fibrous, spotted with pustules, diseased, and shins distorted and awry. Her ankles were thick, her shoulder blades were broad, her knees were big, and her nails were green. Loathsome in sooth was the hag’s appearance.6

This newsletter is getting long, so I’ll stop here. You can google search more examples, if you want them.

Sheela and St. Patrick

I was talking to my husband today about Sheela, wife of St. Patrick, and her celebration day being the day after her husband’s, and he thought I was bonkers; he had never heard that the saint was married, knew nothing about Sheela’s Day, and yet he is born and bred Irish.

In the Roman Catholic faith, priests are not allowed to marry and must remain celibate, but this rule did not come into force until AD1139, 7 so it is not beyond the realms of possibility that Patrick had a wife. If he did, judging by the absence of women in our existing historical record, she was more than likely erased from memory after this date. Fortunately, these efforts were not completely successful; Sheela continued to be immortalised in the oral tradition of Ireland’s folklore.

I’m only bringing her up here because she was childless. At least, there is no record that she and Patrick had children, but that is something else that could have been erased, too. Was she therefore a miserable old cat-lady with no grandchildren to look after?

I highly recommend listening to this masterful episode of

‘s Knotwork Storytelling Podcast to find out more… she’ll have you roaring laughing and wiping away tears at the same time! Enjoy!Sheela and the Sheelanagig

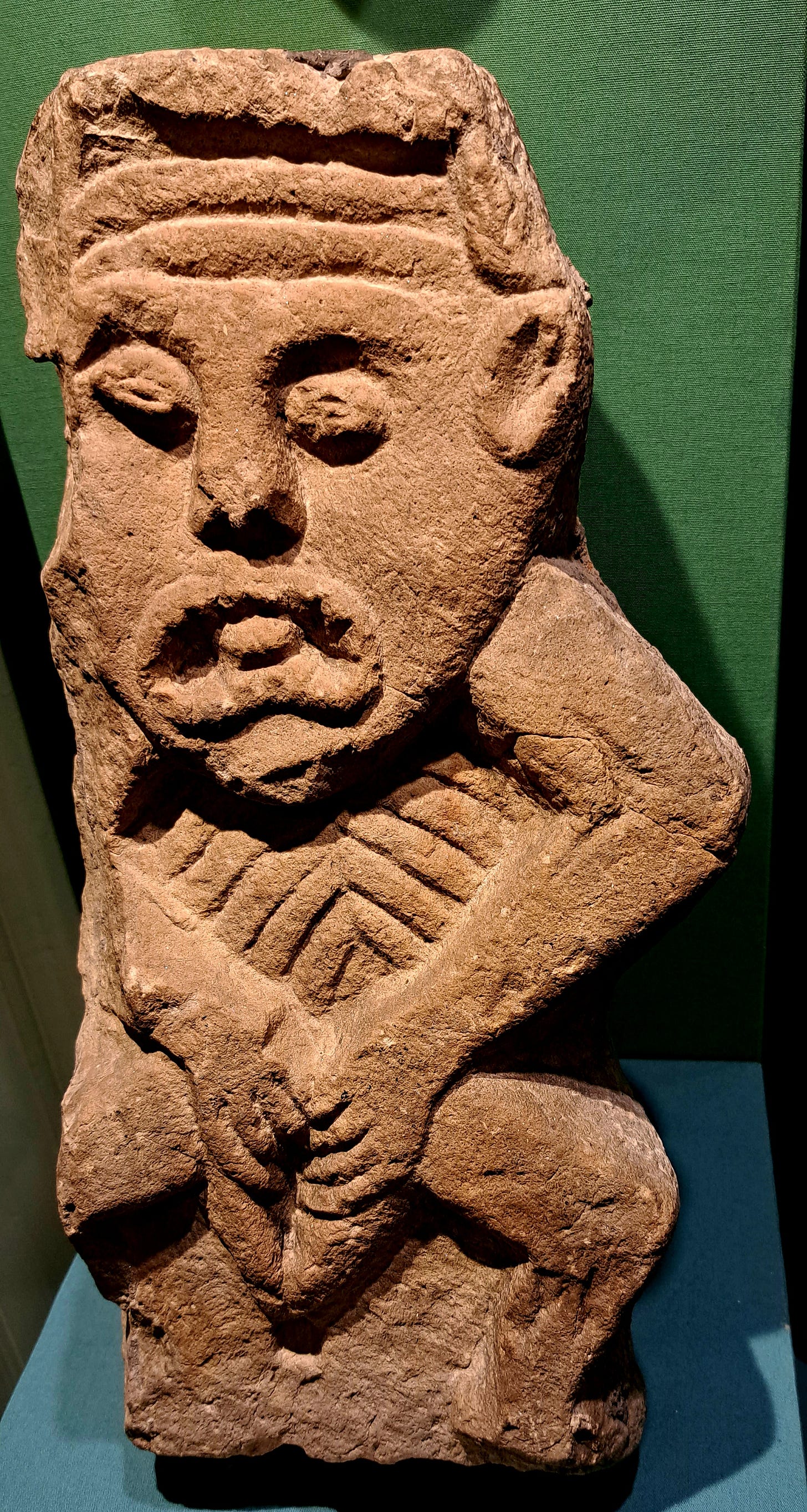

Shane Lehane, folklorist at UCC, equates Sheela with the Sheelanagig. 8 The Sheelanagig is a carving of a female figure using both hands to open and expose her vulva. They are usually to be found on churches dating from the Norman era onwards, which is strange, because Norman stone-masonry is particularly skilled and graceful, whereas the sheelanagig carvings are fairly crude in execution, with a bit of a Medieval caricature vibe about them. Although many theories have been put forward, no one really understands their meaning or purpose.

Lehane believes the sheelanagig is a figure used to be used to teach women about pregnancy and childbirth. Why she would have been placed over church doors and windows is not clear, especially as the church appears to have done its best to erase Sheela from memory. Nor does Lehane explain the reasoning that supports his conclusion. The only connection appears to lie in the name, but surely that’s not much to go on.

Seeing Sheela as an older, childless woman, an Irish native, possibly not a Christian, however, brings me back to Ó Crualaoich’s version of the Cailleach; she fits perfectly into the role of midwife or birthing doula, a wise-woman as bridge, bringing together two belief systems, two cultures, two languages, uniting her people’s traditions and knowledge with that of Patrick’s church.

Also, knowing how shamelessly throughout history the church has co-opted pagan sites, symbols and deities in order to win over native peoples for conversion, I can’t help but feel that these carvings represent pagan divinities, although no pre-Christian versions have been found.

Or have they?

Archaeological discoveries are so often viewed from behind the limited patriarchal lense. Sometimes, the answer we seek is lurking in plain sight but we don’t have our eyes or minds open to receive it. Curious? Check out my post on sheelanagigs here:

September | From Goddess to Grotesque?

Sheela-na-gigs are virtually the only surviving element of one of the most important aspects of the native celtic tradition, [that is] its feminine orientation or belief in the ultimate deity as symbolised in the Cailleach or HAG, the goddess or the image of female spiritual power.

So that’s it for now… wishing you you a very happy St. Patrick’s Day and Sheela’s Day!

The ‘wisdom’ of JD Vance, Desiree Cooper, “My common thread with JD Vance’s Mamaw make his remarks cut extra deep”, MSNBC, 2024.

See Federici’s books, The Caliban and the Witch, and Witches, Witch-Hunting and Women for more information on this.

Lady gregory, Gods and Fighting Men.

Lady Gregory, Gods and Fighting Men.

from the Triumphs of Torlough A.D. 1350 by Seean mac Craith

I love that the word "hag" comes from the Greek "hagia" (holy). A hag is/was a holy woman.

Oh, my dear Ali, thank you so much for weaving my Sheelah into your gorgeous mid-March Cailleach tapestry! I've had the tab open for days, and am finally finding the quiet morning (and the full enough cup of coffee) to spend time with your words.

And thank you for the bit about the Keshcorran caves! I'm not sure if I mentioned my visit there last year... I dreamed them long before I saw them, and I was actually planning on diving deeper into my cave story today. I was thinking of the wolf who took Cormac mac Airt to be raised there for a while and had forgotten about the three hags. Surely they'll have something to say!